TO DO 1: COMMUNICATE AND EDUCATE

by sharing results through repositories and city networks, and by capacity building

Foremost, communication and dissemination of the experiences, not only of successes but also of barriers and failures, are essential for creating the learning environment that allows a wider community to benefit from the outcomes of the demonstration or pilot. Therefore, the sharing of results is an important TO DO that cannot be underestimated. Based on these outcomes, other cities and stakeholders can set up new projects, adapted to their local situations and contexts. The city hosting the original demonstration or pilot, can support such a process by peer-to-peer collaboration with the other city, while city networks as Eurocities and ICLEI can help to disseminate the results in a wider group of cities.

EXAMPLE: STORYTELLING AS A MEAN TO ACCELERATE IMPACT

In URB@EXP, funded by JPI UE, guidelines were developed to facilitate the impact of urban labs. For people and organisations participating it is essential to show the achievements and tangible outcomes of the participatory work in the project. The JPI Urban Europe URB@EXP project found out that “it is crucial that lab practitioners disseminate and anchor the knowledge they obtain about thematic and organisational topics through internal and external storytelling, as a means of sharing and interpreting the experiences gained.” Furthermore, the project underlines that storytelling will help with aligning the participants and that it is a very useful tool to communicate complex information. For external communication purposes, storytelling can be used to disseminate the key results using various media: writing, video, animations and so forth. Storytelling is a crucial practice to ensure the connection between the participants in a project and to create a sustainable community and, on external communication, storytelling of achievements, barriers and bottlenecks within an experimental project can be used for disseminating results, inspiring and therewith, scaling up and replication (Scholl et al., 2019).

EXAMPLE: INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL CAPACITY BUILDING FOR COPING WITH COMPLEX PROBLEMS

Education, training and the distribution or sharing of knowledge has been found to be essential in experimental projects, according to JPI UE project URB@EXP (Scholl et al., 2017). Internally, the project partners need to strengthen their capacities with new social and personal skills in order to co-design, implement, manage, communicate, mediate, negotiate, facilitate, resolve conflicts and learn from their activities. Externally, public institutions and administrative structure can learn how to manage the interests of various stakeholders in complex relationships. The capacity building involves the development of partnerships, inspiration, exchange of skills and knowledge, networking and sharing information as well as innovative methodologies.

EXAMPLE: QUOTES FROM VIENNA EXPRESSING POSITIVE VIEWS ON THE LIGHTHOUSE PROJECT

Informal communication about the results of the project or action plan is very important for potential replication and upscaling. The quotes below make clear that the results are highly valued.

Michael Castellitz (BWSG, a Limited-Profit Housing Association):

„An important aspect for us is social justice and we are proud to be able to provide ecologically sustainable mobility to our residents in the Hauffgasse (housing complex).”

„The BWSG has launched a pilot project with the e-car sharing Hauffgasse, which has not yet taken place in this form in non-profit housing. We even like it so much that we consider implementing the project in other projects. "

Markus Zagermann (resident/user/active group member):

„The active group is really promoting the neighbourhood, the sense of togetherness. "

Nathalie Gmeindl (resident/user/active group member):

„It is a nice feeling that you know a few people right away."

Gerhard (resident/user/active group member):

“I've been living in this housing estate since 1982 and now with this refurbishment and the possibility of having electric mobility available to lend, I thought, I'll take a look at that, that sounds good. "

„This is really fun and is also green, impossible to have it greener. "

EXAMPLE: TRANSFER OF KNOWLEDGE FROM DEMONSTRATOR CITIES TO CELSIUS MEMBER CITIES

CELSIUS worked very successfully with knowledge transfer in several ways:

- The online wiki-based CELSIUS Toolbox gathered information from the project’s demonstrators, as well as contributions and research from other actors in the network, including other EU-projects, academic institutions, and industry actors. The wiki format means that the accumulated knowledge is expanded, linked, and refined. It also allows users to hone in on the particular topic they want information on. As the needs and challenges of cities differ, the same information will not be relevant for everyone. The wiki-format means that city representatives can search for what they need, and even have the opportunity to report back by contributing their own results to the wiki;

- Dedicated workshops and conferences – these have often focused on a specific topic, related to the demonstrators or other expertise within the project;

- Webinars on specific topics. Some have focused on results from the demonstrators while others have presented solutions based on needs that CELSIUS Member (follower) Cities have identified. These are open to all Member Cities and other members of the network, recorded, and put up on the CELSIUS Toolbox wiki afterwards;

- Uploading of CELSIUS monitoring data to the SCIS platform;

- Participation in a District Heating and Cooling network with many different kinds of stakeholders involved. This allows for needs-based and spontaneous knowledge transfer and for concrete further steps to be taken outside of formalized CELSIUS activities (e.g. some cities in need of companies or expertise might learn of where this is and then establish contracts outside of the CELSIUS activities).

Supporting CELSIUS Member Cities involved a combination of categorisation/generalisation and tailored solutions based on an ear-to-the-ground approach. Different contexts fostered expertise in certain areas, and it required imagination to be able to use knowledge in different contexts. Peer-to-peer learning with discussions where both parts need to learn, proved to be successful, although time-consuming while it needs to be combined with support at system level.

ETIENNE VIGNALI

Project Manager Lyon-Confluence:

Project Manager Lyon-Confluence:

“Thanks to the Smarter Together project…… we have made important progress for tackling energy challenges in the Lyon-Confluence urban project » … we have strongly increased the production and distribution of renewable energies, the energy renovation of buildings, the development of electric mobility solutions and the data management for improving the environmental performance the Lyon-Confluence urban project “

TO DO2: DEFINE THE BUSINESS MODEL

in terms of durability and resilience in future, and financial resources for scaling up

Within the city that hosted the project, usually successful implementation is followed up by creating the right preconditions for repeating the project within the city administrations’ jurisdiction. Therefore, the next TO DO entails that the business model in terms of durability and resilience must be defined, and financial resources for expansion, scaling up or replication ensured.

EXAMPLE: SUSTAINING THE INNOVATIVE PROJECT

Once the end of urban living labs and other experimental projects comes in sight, usually the question arises what will happen with the network, experiences and knowledge created in the project and how to continue. This applies to the aim of continuing the experimentation; using the knowledge and experiences that have been generated in the lab rather than scaling a certain solution. URB@EXP has defined several scenarios for the future of urban labs once the initial project ends (Scholl et al., 2017):

- Continuation of the lab: Continuing with the original operation without changing the model or the organisational structure;

- Expansion of the lab: Increase in people involved in the urban lab and financial resources;

- Replication of the lab: replicating the lab principles and working procedures in a completely different institutional setting: different municipal departments, stakeholders, urban actors;

- Integration of the lab: Embedding the principles, practices and knowledge applied and generated in the lab into urban governance structures. This implies a permanent behavioural change in the administration of cities.

EXAMPLE: CITIZENS HELP TO SHAPE NEW BUSINESS MODELS FOR E-CAR SHARING IN VIENNA

Smarter Together took advantage of the refurbishment process in Vienna to anchor other innovative actions. Car-sharing e-mobility is a part of the refurbishment process and brings additional value to both the BWSG, a Limited-Profit Housing Association, and the tenants. The close co-operation with the mediation institute (wohnbund:consult) located on the site, provided the human resource base for communication and motivation. This organisational set up was a clear win-win situation for all involved. The motto was: Change must happen, refurbishment has to be done, let’s make it smart. The EU funded project was a good innovation trigger. Credibility was at the core, the EU funding essential for making a first showcase. A professional car-sharing provider was essential in the set up (Caruso). Soon after the initial information phase, a group of highly motivated pioneers among the tenants with quite some technical skills, became involved in the initial project design and choice of the three e-car models that were to be acquired. This group currently also handles the everyday management supporting Caruso, while it provides valuable feedback on and inputs to the implementation phase of the pilot project. The group is also involved in the design of the final business case. All professional stakeholders identified e-car sharing in a Limited-Profit Housing Association as an interesting business case and are developing it further now in other projects (upscaling during the process). An additional result, though not expected at that level beforehand, was the aspect of social integration and local social dynamics triggered through the e-carsharing. The latter appeared to be of a major interest for the Limited-Profit Housing Association (Smarter Together, 2019d).

WHY?

To really support transitions towards sustainability and liveability and to limit risks related to wicked issues, the solutions, innovations and research results have to be grounded in urban contexts and systems.

What has been observed in recent years is that technology and solutions have been developed and are available, but that the experiences and knowledge created in these demonstrations or pilots were not being sufficiently contextualised to achieve a (regime) change on a larger/broader scale.

One reason is that traditional business models are often not useful for experimental urban sustainable and smart development projects. Traditional business models might be challenged by new models for urban sustainable development. Therefore, new business models could work against the interests of long-established businesses. Consumers becoming pro-sumers, can pose a threat to existing, well working business models. For example, business models which allow a decentralised production of energy by individual households, might go against traditional business models such as energy production by coal, atomic energy, and so forth. The interests of organisations benefitting from these traditional models, might not support the uptake and wider distribution of such novel products and processes. At the other hand, the coming int existence of new value chains might lead to new business models.

TO DO 3: DEVELOP A PLAN FOR WIDER COLLABORATION

with industry, ICT companies, solution providers, citizens, local businesses and research after the demonstration or implementation

The next TO DO for this stage, is that a plan needs to be developed which consolidates wider collaboration of the city with industry, ICT companies, citizens and local businesses after the demonstration is finished. This could be for example with representative organisations of specific stakeholders, such as housing associations and grassroots initiatives, branch organisations of professionals, or associations of local government.

EXAMPLE: COOPERATING WITH KNOWLEDGE CENTRES AND LIKE-MINDED INITIATIVES

In JPI UE project URB@EXP it appeared that knowledge centres are important actors who have the capacity to facilitate social learning processes and stakeholder engagement. They also help to bring the lessons learned and the knowledge generated in urban labs into decision-making and agenda setting processes. Further, connecting experimental projects with local (grassroots) initiatives and activists can help to implement transformative processes. In addition, networks bringing together governmental institutions, and bottom-up initiatives and local activists, on regional, national and transnational scale, support the exchange of knowledge, lessons learned and consequently enhance the impact of the experimental projects (URB@EXP, 2019).

EXAMPLE: UPSCALING OF INNOVATIVE APPROACHES IN HOLISTIC REFURBISHMENT OF HOUSING AND TENANT’S PARTICIPATION IN OTHER SOCIAL HOUSING BLOCKS IN VIENNA

Holistic approaches to urban renewal are at the heart of energy and resource savings. Vienna’s Smarter Together approach is process-oriented and inclusive with respect to all actors. It combines a bottom-up learning and a top-down decision-making process. Crucial is not a specific activity itself, but the learning process, the trust built up and the motivation of all actors including government, Limited-Profit Housing Associations and tenants. This approach helps government, housing management, institutions dealing with the dialogue with the tenants as well as tenants themselves, to become and stay motivated and empowering them to make their own respective contribution to climate action. Through interaction, the different actors take over responsibility and are given the tools to make a change. Upscaling of Smarter Together solutions in Vienna is a result of this process and done by the actors on a variety of levels:

- The Limited-Profit Housing Associations integrate knowledge, skills and motivation gained throughout the process, and scale it up through other ways of management within their own enterprises;

- The gained competitiveness becomes a showcase for other Limited-Profit Housing Associations within the Austrian umbrella organisation GBV;

- The City of Vienna as social housing provider integrates new experiences, skills and methods through the implementation of the pilot project. Upscaling is done during the process by including a variety of departments and units;

- Upscaling is especially ensured within the institutions which take part in the project, that are dealing with the dialogue with tenants (private and public);

- A specific way of up-scaling up the projects’ results is taking place by integrating skilled project management staff, experienced in the Smarter Together project, in a strategic position in Vienna Housing (owning 220.000 municipal flats, accommodating 25% of Vienna’s population).

The legal framework and desirable innovations are tackled through inclusive project management and process (Smarter Together, 2019d).

EXAMPLE: ADVANCED DECISION SUPPORT FOR SMART GOVERNANCE

SmartGov (2019) aims to create new governance methods and supporting ICT tools that simulate the impact of policies on urban planning in Smart Cities. Furthermore, the project supports two-way communication with large stakeholder groups. ‘Smart Cities’ provide new ways of designing and managing public services, infrastructures and buildings, sustainable mobility, economic development and social inclusion. However, communication between citizens and urban policymakers is hardly bi-directional, partly because citizens’ social media feeds and useful open data sets are underutilised. New modelling and visualisation tools were developed that effectively incorporated linked open data and social media into Fuzzy Cognitive Maps, for discussing policy scenarios between citizens and governments. The tools have been tested in four cities: Limassol, Quart de Poblet, Vienna and Amsterdam.

EXAMPLE: LEARNING PROCESSES AND CHANGES IN BEHAVIOUR FOR REDUCED ENERGY CONSUMPTION

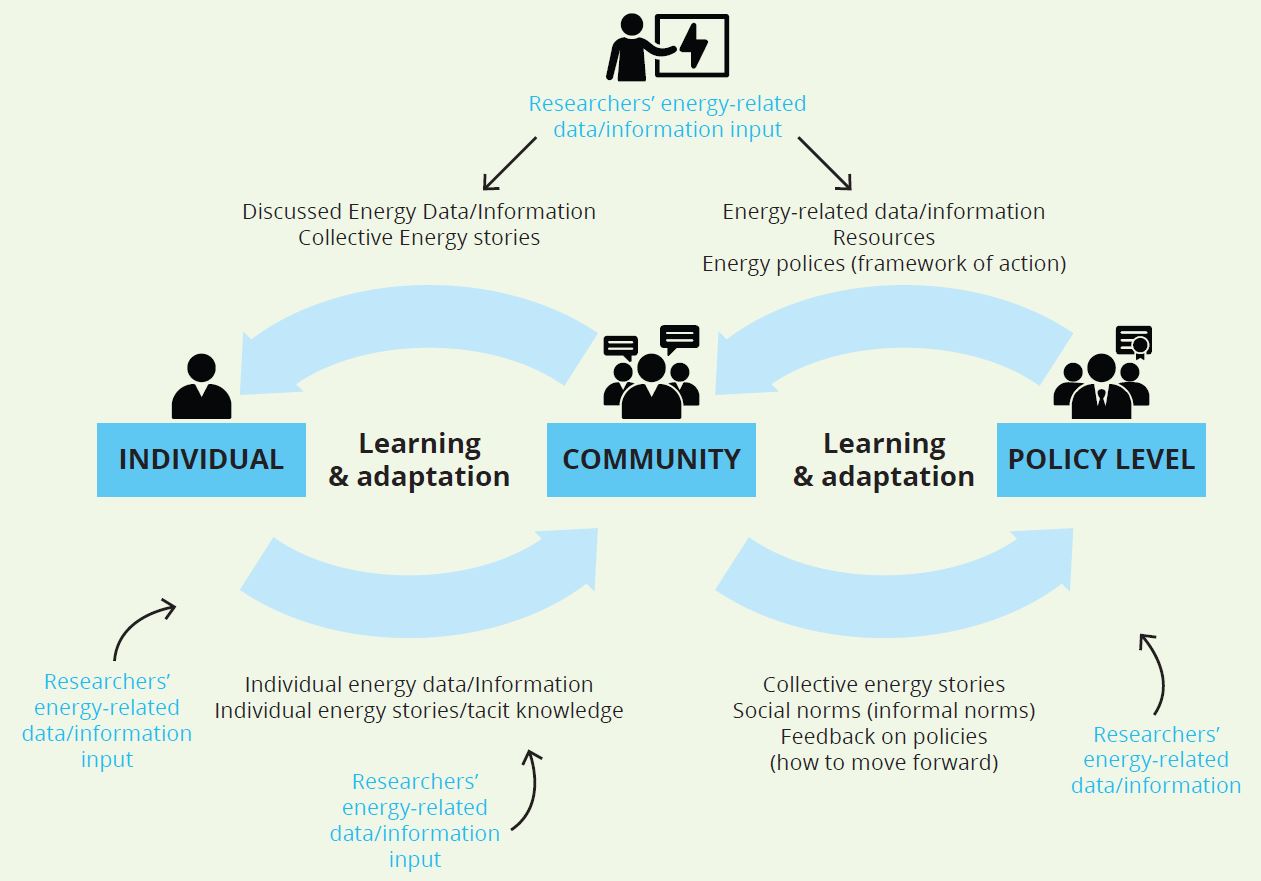

Although tremendous progress has been made in technological innovations for saving energy, the average energy consumption per household in Europe has increased in the last few years. The primary goal of CODALoop is to achieve positive changes in behaviour of residents (CODALoop, 2019). To achieve this goal, urban living labs in Amsterdam, Graz and Istanbul have been set up to gain an in-depth understanding of the learning processes and behavioural changes needed to reduce energy consumption in cities. An online platform has been developed which allows users to monitor the implications of their behaviour (in housing, mobility, consumption and recreation) on the energy consumption compared to the average consumption in the district. The diagram below illustrates the learning and adaptation loops which are established in the urban living labs: Generating ‘Data to Individual’, ‘Individual to Community’ and ‘Community to Policy’ learning and adaptation feedback loops through designing and testing support software for data-sharing and social interaction.

By using a mix of co-creation methods and involving residents in three urban living labs the project will develop a conceptual understanding of data-driven feedback loops. These enable learning and behavioural change in energy choices, a marketable software platform for data-sharing, and social interaction about energy use and policy innovations for energy transition.

WHY?

Current governance structures and processes are often challenged, as new types of collaboration and learning are tested in the often rather experimental setting of such projects.

By bringing urban actors, stakeholders, civil society and so forth, together to jointly work on a specific topic, demonstrations or pilots allow the development of new urban collaborative governance concepts and policymaking frameworks, besides new approaches to urban planning and development, based on productive and creative stakeholder engagement. This collaboration must to be widened and consolidated for several reasons:

Integrated and functional long-term governance structures need to be maintained beyond the project’s end. Experimental projects provide a framework for collaboration of various administrative sectors and departments, businesses, research institutes and civil society. Within the projects, an environment which allows participants to jointly discuss and exchange has been created and a local ecosystem with new connections and networks has been formed.

Experimental projects provide the testing ground to create evidence with foreseeable risks. A major advantage for public agencies of demonstrations or pilots is that the risks the experimenting comes with, can be taken and tested on the scale of a (often subsidised) project. Narratives behind the project, coupled with facts and figures, provide the ground for identifying the public value of the project and contribute to trigger decisions and investments for the replication and scaling up of the results and processes of demonstrations or pilots.

The openness of the current governance regimes to experimentation is essential. The level and depth of experimentation is closely connected to the specific type of governance setting, flexibility and openness to new approaches and processes. In some European countries, city administrations and public bodies have a tradition and openness towards experimentation and the acceleration of the results while in others these approaches are very new.

What is more, participation through co-creation precedes in many cases more formal collaboration. Today, it is widely acknowledged that real participation of citizens, organisations and other urban actors, is essential for experimental urban research and innovation projects as well as for urban transition to a more sustainable and resilient future state (JPI Urban Europe, 2018; EIP-SCC, 2016). Participation should be taken seriously and should start right from the beginning of a demonstration/pilot/project/urban living lab having the prospect of acceleration in mind.

Creating ownership of all stakeholders and people involved in a dedicated process, sets cornerstones for later acceleration of the impact that was generated in an experimental smart, sustainable cities project. Bringing all stakeholders together from the beginning, collecting their ideas and listening to them while explaining the objective of scaling up or replicating the results at the end of the project right, is crucial. A moderated and clear process must be set up, in which the acceleration of the impact generated in the demonstration or pilot, is stressed right from the start of the project. Participating citizens are experts in their living environment, street and neighbourhood. Therefore, both individuals and associations can act as multipliers, who are widening the circle of engagement. This leads not only to a better understanding of complex settings and contexts, but it also generates more robust and innovative knowledge, and forges better connections between social and technical developments in cities.

TO DO 4: PERFORM A VIABILITY ASSESSMENT

of applied methods and solutions for other projects and contexts, and do a risk assessment of key success factors

Probably, the successful implementation of the demonstration or pilot will draw the attention of other parties interested in repeating the demonstrated solutions in other places and in other situations. However, as solutions cannot be simply copy-and-pasted, for the next TO DO their applicability and viability in other contexts should be assessed, and key success factors must be compared with the new situation before the plan is prepared.

EXAMPLE: SELF-ASSESSMENT METHOD FOR REPLICATION

One of the first steps and key requirement for becoming a Smart City is to set up an effective and ideally permanent City Governance involving all city relevant departments (Energy, Mobility, ICT, Waste management, etc.) as well as key community groups (utilities, industry, SMEs and start-ups, research organisations, NGOs, citizen associations). The governance aims to facilitate communication and collective thinking across municipal sectors and between the municipality and the local community, thereby breaking static silo approaches, and disconnection from society, and unleashing strategic, integrated and synergetic smart city planning. In this context the notion of “cooperation” gains relevance. Generally speaking, cooperation can be interpreted as working together with a common purpose and toward a common benefit. In RUGGEDISED, ISINNOVA a specific methodology was developed for the evaluation of the perceived level of cooperation inside each City Governance and the improved capacity acquired by its members. It is a useful method to assess the “effective” functioning of the group and to identify potential “weak points” for future improvement. The method is a self-assessment process carried out directly by the staff of each Fellow City, with ISINNOVA providing assistance and guidance in the use of the method and interpretation of the results.

Level of Cooperation

In RUGGEDISED, the “level of satisfaction with cooperation” is closely monitored. To be able to assess and quantify this qualitative indicator in the best way, the project built upon the work carried out by the project CITYKeys, which compiled a complete and exhaustive set of KPIs, and further developed and validated a custom-tailored set of KPIs to allow for common monitoring and comparison of smart city solutions across European cities. Focus was on the following six indicators, adapting them to the specific needs of the RUGGEDISED work: Leadership, City Departments Involvement, Balanced Project Team, Clear Division of Responsibility, Stakeholders Involvement, Interoperability. The level of cooperation within City Governances can be quantified by combining these 6 dimensions: the assumption is that the more successful they are, the higher the level of cooperation will be. KPIs are assessed via ad-hoc questionnaires created by ISINNOVA and submitted to the members of the City Governances core teams, expert groups and decisions groups (these are the three key bodies which were adopted by the Fellow Cities to foster the work of the respective City Governances), as well as with other relevant community stakeholders involved in the joint execution of the Smart City Replication Plans of Brno, Gdansk and Parma. The assessment is executed in two specific moments in time:

- At the beginning of the project, in order to build a baseline and an ex-ante evaluation of city expectations (results of this assessment are attached to this report);

- At the end of the project, when an ex-post evaluation and a comparison with the ex-ante expectations and across the three Fellow Cities will be done. This will in turn allow to identify the main barriers and success drivers to improve cooperation.

Smart City capacity level

Similarly, a self-assessment on the governance capacity level is performed at the beginning of the project on the following horizontal dimensions (see EIP-SCC, 2013):

Decisions:

- Policy and Regulation: creating the enabling environment to accelerate improvement.

- Integrated Planning: working across sectors and administrative boundaries and managing temporal goals.

- Citizens Focus: involving citizens in the process as an integral actor for transformation.

Insights:

- Knowledge Sharing: accelerating the quality sharing of experience to build capacity to innovate and deliver.

- Metrics and Indicators: enabling cities to demonstrate performance gains in a comparable manner;

- Open Data: understanding how to exploit the growing pools of data; making it accessible- yet respecting privacy.

- Standards: providing the framework for consistency commonality and repeatability; without shifting innovation.

- Foresight: understanding how to develop long term smart city visions, roadmaps and plans using participatory foresight methodologies.

Funds:

- Business Models, Procurement and Funding: identifying sustainable models and integrating local solutions in an EU and global market.

WHY?

As cities are complex and highly dependent on local characteristics, scaling up and replication of demonstrations and pilots is a tricky but important issue. On the one hand, the settings and circumstances in such sometimes experimental projects are specifically arranged for the course of the project and might not necessarily fully reflect the urban realities.

On the other hand, plans and activities might be dedicated to the characteristics in one particular city, district or neighbourhood making the direct application in another setting difficult. As pointed out earlier in section 7.1, because the local characteristics determine the translation of results, findings, and so forth, into another urban context, it is useful to mention the framework conditions influencing these processes for enhancing the impact of the demonstration or pilot from the development stage on. In practice the interplay of the various framework conditions for business models, participation and governance, determines whether, and how far the current urban system is able to take up new results and solutions (EIP-SCC, 2013).

TO DO 5: ADJUST APPLIED METHODS AND TECHNOLOGIES

towards local situation and conditions, and to foreseeable changes in future

Subsequently, the next TO DO is that the original plan and project features must be made replication and future-proof, by adjusting it to other local situations and conditions, and to expected changes in future.

EXAMPLE: URBANIST STUDY ŠPITÁLKA

The City of Brno launched an urban design competition for its replication area. The task for the participants in the International Open Urban Design Idea Competition for Špitálka was to convert a part of the unused premises of the Brno district heating plant and the surrounding area into a smart city district. The results were approved by the Brno City Council on Wednesday 20 March 2019. The competition designs also had to take into account several principles of Smart Cities, making the new neighbourhood environmentally friendly and self-sufficient as regards energy consumption. The objective is to verify new technologies and innovative approaches that could subsequently be expanded also to the rest of Brno. The Špitálka district could thus serve as a testbed for further city development. The competition was announced as an idea competition. Thus, the City of Brno now can use the ideas of the highest-appraised proposals (not only the winning one) for commissioning a planning study of a broader territory. This will then be used for an amendment to the Master Zoning Plan of the City of Brno and for the very construction and revival of this part of the city.

WHY?

As mentioned in section 7.1, it is hardly ever possible to just copy-and-paste specific solutions to other situations and contexts. Therefore, a profound review of the original plan of the demonstration project is necessary: which adjustments and fine-tuning are necessary to achieve the aims of the new project?

TO DO 6: CONSOLIDATE A PIPELINE OF NEW PROJECTS

in other cities with other contexts and local specific cities

Based on these outcomes, other cities and stakeholders can set up new projects, adapted to local situations and context.

EXAMPLE: REPLICATION IN PRACTICE WITH A PASSIVE CITY HALL IN SERAING

The passive city hall of Seraing is part of a global reflection on the requalification of an 800 hectares’ zone in the city. This area, hard hit by the steel crisis, has been the subject of a vast program of studies on a magnitude never seen before in Belgium. All the actions were completed by a town planning study, the result of which gave birth, in 2006, to the Master Plan of Seraing. Among the priority intervention zones identified, the regeneration of the city centre as well as the construction of a new City Hall, were the first step towards the redevelopment of the city.

The construction of this new building is also part of a sustainable development objective that supports the commitments made by the City of Seraing in the framework of the Covenant of Mayors through its Climate Action Plan, adopted in 2015, to reduce the CO2 emissions to 20% by 2020. It is from this perspective that the city has opted for a passive building, at the forefront of technology, home automation and construction techniques. The main objective is to reduce the consumptions by 80% previously measured using the old, expensive, and energy-consuming buildings disseminated in the city. The new City hall of Seraing is the first and largest (6,345 m²) public building to be certified passive in Wallonia. It has been inserted into a public space that has been entirely redesigned. In addition to building performance objectives and passive certification, other objectives have been achieved, that makes it a replicable model across other European cities: a significant financial gain through reduced energy bills compared to old installations and travel minimized by bringing together many city departments, an ease of maintenance and operation of the building, the beginning of the regeneration of the city centre as the city is keen to encourage private investment via a newfound attractiveness.

The high performance represents an average saving of € 40,200 per year, as well as an avoided emission of 148 tonnes of CO2 per year, compared to a new building that strictly complies with current standards. The construction of the City hall has been the subject of a loan of € 10 million contracted by the City of Seraing and supported by an alternative financing of Wallonia of € 7.8 million.