Urban platforms

According to the EIP-SCC initiative Urban Platforms, an Urban Platform is a way to disclose a logical data architecture of the city that connects and integrates data streams within and across city systems, in a way that uses modern technologies (sensors, cloud services, mobile devices, analysis, social media etc.). An Urban Platform helps in implementing integrated planning related strategies and roadmaps by providing some basics for cities to quickly move from fragmented to holistic operations, inclusion predictable operations and new ways of involving and serving city stakeholders; It can contribute to making results tangible and measurable (e.g. increasing energy efficiency, reducing traffic congestion and discarding, developing (digital) innovation ecosystems, effectively managing city activities for

administrations and services), by providing the necessary infrastructure for organised and robust collection of data. The proposed Urban Platform is an open shared architecture that is used to collect, manage and share city data, which are stored in the cloud. Figure 3.1 shows an overview (EIP-SCC, 2016) Urban platforms are mostly funded by the city, but sometimes regional and central governments can also be involved. The EIP-SCC designed an urban platform that is fully based on requirements coproduced by the ten involved cities, on an open architecture, and on standardisation frameworks.

The EIP-SCC Urban Platform initiative developed three resources: A Management Framework, Requirements Specification for Urban Platform, and Standards. The Management Framework is a very comprehensive set of practical and organised methods (e.g. templates, tools, value and business cases) which can be used together to identify, redirect and enhance the quality of the cross-domain and integrated city data management methods. Figure 3.2 illustrates the logical path that the city must follow in order to create the framework (BSI, 2016).

The Requirements Specification for Urban Platforms was created by the core group often cities to assist to others in the development of their own platform specifications; the cities - London, Amsterdam, Berlin, Gent, Barcelona, Murcia, Valencia, Derry, Mannheim, Copenhagen, Scottish cities, and Southern Italy. The document identifies an explicit set of technical (e.g. related to standardisation) and non-technical (e.g. policy-related results) requirements (BSI, 2017).

In addition, in consistency with the present Smart City Guidance Package and its related set of steps, ISO TC 268 is developing a standard on Management guidelines of open data for smart cities and communities, in support of/complementary with the implementation of its management system standards ISO 37101 and all related 371xx series of standards.

Citizen engagement

This section explains how to successfully involve citizens and other stakeholders, such as local businesses, in the planning and implementation of smart city projects. Many examples demonstrate the best practices in this field.

Participatory Budgeting

Participatory Budgeting (PB) is a form of participatory and inclusive democracy that empowers residents, which engages them in finding solutions responding to their needs and knits communities together. By bringing people together, the latter can learn, debate and deliberate about the allocation of public resources; for this reason, PB is considered to be a form of participatory and inclusive democracy and as a key element of the next generation of democracy. It began its journey in Porto Alegre, Brazil, back in the ‘90s. Throughout the years, it has proven to be a powerful enabler allowing citizens to contribute as actors of their own city’s administration. Since its launch, European examples of Participatory Budgeting have increased from 55 to over 1.300 with over 8 million citizens actively involved in PB today and 3 thousand cities and municipalities implementing PB.

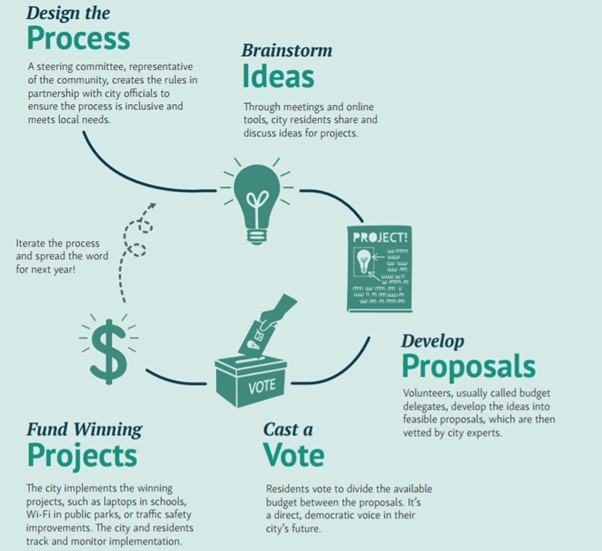

PB involves an annual cycle of meeting and voting, integrated into the broader budget decision-making process, which follows five steps: 1) Process Design; 2) Idea Brainstorming; 3) Proposal; 4) Voting and 5) Winning projects Funding (Next Generation Democracy, 2016).

Participatory Budgeting procedures are characterised by three specific features:

- Explicit discussion of public expenditures, followed by the project’s entry into deliberation, process where local authorities are engaged

- Co-decision as a binding element of public decision-making

- Proposals developed by citizens (or groups), voted and implemented in a continuous loop of feedback loop from and to citizens.

This new practice has demonstrated it motivates broad civic participation, it engages a true cross-section of the community, makes people feel inspired and active, and it supports communities in becoming more resilient and connected.

Participatory Budgeting as an EIP-SCC Marketplace Initiative

Being the focus of the Citizen Focus Action Cluster the civil society, industries and different layers of government working together with citizens to realise public interest at the intersection of ICT, mobility and energy in an urban environment, the cluster gathers three initiatives promoting activities across European cities to ensure the active role of citizens in smartened-up cities.

Given the digitisation of cities and the development and take up of new leadership methods across cities, the action cluster has recently launched a dedicated initiative on Participatory Budgeting for Inclusive Smart Cities and Communities to foster knowledge sharing and capacity building across Smart Cities. The initiative, aims at defining scenarios to use PB and pilot cities to define best practices to be replicated on a larger scale. Technology solutions for PB are also of crucial importance for the initiative, which is indeed dedicating several knowledge sharing activities to this topic, and are meant to be included in the dissemination of best practices, after the piloting phase.

Participatory Budgeting in the e-Government plan

Many cities have been increasingly using on-line digital tools to implement PB, either through in-house designed or Open Source or proprietary platforms.

The implementation of a digital Participatory Budgeting process requires a number of core functions for carrying out the standard phases of a PB process. These functions relate to the collection of ideas, technical analysis, selection and monitoring. The majority of these platforms includes a CMS[1] for the management of top-down communication regarding the advancement of PB processes.

Platforms are, in a way, a subset of the larger category of collaborative platforms for social innovations developed and diffused during the last years and this provides Participatory Budgeting the opportunity to feed into e-Government plans and actions.

How can we move from planning to implementation? By supporting the delivery of PB processes through ‘standardisation of methods’ activities, putting emphasis on PB within the eGov action plans, creating a knowledge-sharing online platform and conducting research activities to discover new domains in which PB could be implemented.

EMPATIA platform

Organisers and participants in today’s PB processes have started to benefit from a range of ICT enhancements, including those offered by the public sector (e-government tools and open-data policies), and from increased access to online media and social networks. EMPATIA (Enabling Multichannel Participation through ICT Adaptations), a 24 months project, seeks to radically enhance the inclusiveness and impact of PB processes, increasing the participation of citizens by developing and making publicly available an advanced ICT platform for participatory budgeting, which could be adapted to different social and institutional contexts. In so doing, it will support the complete life cycle of budgeting processes in various cultural and political contexts. The underlying expectations of EMPATIA are creating and advocating processes of democratic deliberation and decision-making; contributing to intensify participatory democracy practices in which citizens decide how to allocate part of a municipal budget or other budgets of public interest.

In order to achieve this ambitious goal, EMPATIA will operate on two main lines: producing outputs for facilitating and improving the relation between experimental administrations and their citizens, and providing tools capable of increasing the efficiency of Public Administration offices in their interaction with the participatory decision-making space.

Privacy Management Guidelines & Good practices

Context or privacy in smart cities

The management of privacy will be a major concern in smart cities. First, compliance with GDPR was enforced in May 2018. Secondly, smart city authorities will have to deal with complex ICT ecosystems as shown in the figure below:

- Smart city authorities will have to interact with its citizen on privacy issues

- Smart city authorities will have to deal with stakeholders such as operators, integrators and suppliers. Operators, as data controllers or data processors will have specific privacy obligations such as privacy impact assessment (PIA) or privacy-by-design (PbD)

Two recommendations are made:

- Recommendation 1: Engage within the smart city community to share concerns and experience of privacy management

- Recommendation 2: Converge towards common practices concerning privacy management.

The rationale for the recommendations is the following:

- It will create a common body of knowledge

- It will speed up GDPR compliance

- It will contribute to interoperability by allowing cities to exchange, reuse applications with the same level of privacy management practice.

Actions

In order to support the recommendations the citizen approach to data: privacy-by-design initiative was set up by EIP-SCC. The following activities have been set up:

- Awareness workshops with the objective of promoting engagement

- Privacy impact assessment workshops with the objectives of sharing practices on privacy management.

- Participation to standardization through the PRIPARE 7001 commitment to EIP-SCC. PRIPARE, initially a support action funded by the European Commission on privacy-by-design, has a liaison category C with ISO/IEC JTC1/SC27/WG5. It has led to the submission of a new standardisation of work within the “privacy in smart cities” sector.

Good practices and tools for citizen engagement

Based on a continued knowledge sharing process with the Citizen Focus Action Cluster, several tools and projects have been identified which are acknowledged as good practices to inspire integrated planning in Smart Cities.

Smarticipate. Opening up the smart city

Funded by H2020 -INSO-1-2015 an enabled open government web platform that allows interested citizens to support the decision making process. Smarticipate is a powerful new tool that addresses these issues and makes co-creation easier for city administrations. Features like a 3D model builder, automated feedback, the possibility to plug in different data sets or share proposals on social media are just some of the elements that can help facilitate cutting edge co-creation processes. The tool is being developed and tested by the City of Rome, the City of Hamburg and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, with the support of a consortium of technical experts from across Europe. The Smarticipate platform makes open data available to citizens in an understandable format. By doing so, it has the potential to transform open data from a little used resource to a vital tool to plan the future of a city.

Through the platform, users are able to see proposed urban planning changes on a 3D map of their city. If the user has an idea to improve the proposal, they can make the change directly, observing their alterations in real time. Other users can also see the new proposal and comment on it.

If potential changes violate any legal or policy barriers, the intelligent system will inform the user and gives detailed reasons based on the data provided. In addition to making changes to urban design, citizens will be able to feed in data from their own locality, improving data sets.

WeLive. A new concept of public administration based on citizen co-created mobile urban services

The WeLive project is devised to transform the current e-government approach by facilitating a more open model of design, production and delivery of public services leveraging on the collaboration between public administrations (PAs), citizens and entrepreneurs. WeLive applies the quadruple-helix approach based on the joint collaboration of 3 PAs, 4 research agents and 5 companies, constituting the consortium, plus citizens to deliver next generation personalised user-centric public services. WeLive aims to bridge the gap between innovation and adoption (i.e. take-up) of open government services. For that, it contributes to the WeLive Framework, an ICT infrastructure which adapts, enhances, extends and integrates Open Innovation, Open Data and Open Services components selected from consortium partners’ previous projects. An Open Innovation Area is proposed where stakeholders collaborate in the ideation, creation, funding and deployment of new services. A Visual Composer enables non-ICT users to assemble public service apps from existing blocks. Stakeholders uploaded/sold and downloaded/purchased the generated apps to/from the WeLive Marketplace, thus imposing economic activity around public services. Personalisation and analytics of public services are done through collaboration of the Citizen Data Vault, which manages personal information, with the Decision Engine, which matchmakes user preferences, profile and context against available public services. Two-phase pilots have been conducted in 3 cities (Bilbao, Novi Sad and Trento) and 1 region (Helsinki- Uusimaa) across Europe. Further, the business feasibility and commercial potential of the WeLive Framework, including its individual assets, was validated by developing and deploying sustainable business models.

Smart Cities Lighthouse Projects

The Social dimension has been taken into consideration across SCO1 projects and several of the collected best practices in demonstration sites in lighthouse cities have shown how citizen engagement has proven to be one of the success factors across several projects and sectoral areas (mobility, retrofitting & energy), while in others difficulties in involving citizens have hindered the full project’s potentials to be exploited.

In SCC-01 projects focused on retrofitting, it was demonstrated how the involvement and consultation of tenants was crucial to reach the objectives, like in the REMOURBAN Project pilot in and the SmartEnCity in Tartu (FI) and Sonderborg (DK).

A comprehensive approach to citizen engagement was featuring the SmartEnCity project in Victoria Gasteiz. As part of a citizen engagement plan, “a qualitative research has been developed to map the citizen engagement reality, which is called the Citizen Engagement Strategy Model. The purpose of this model is to create a frame that can be useful for cities that are developing citizen engagement strategies involving the offer of innovative services and products. Additionally, the Communication and Citizen Engagement Committee was created within the governance structure of the Vitoria-Gasteiz’s lighthouse project in order to promote and guarantee the community involvement and citizen engagement. The engagement activities in Vitoria Gasteiz include the involvement of the neighbourhood associations; door-to-door invitations to a meeting presenting the project; an exhibition for the residents of the refurbishing typologies, as well as a demonstration of how the connection to the district heating will take place; identification of lead users or early adopters who will be offered some workshops where they can learn from the experiences of other renovation projects, and be given the opportunity to visit the projects. The tenants are being continuously informed about the benefits of the project through the information office opened within the Coronación district, and through specific dissemination actions that take place periodically to strengthen neighbours’ engagement. Ad hoc dissemination material has also been created and distributed among the tenants. Another important point related to communication with the stakeholders is that, as a rule, there is a single interlocutor with each community making the communication much easier and more direct, so that each community always talks with the same person to manage all the issues related to the project” (SCIS, 2017).

The Inclusive Manifesto on Citizen Engagement

The EIP-SCC Action Cluster on Citizen Focus has launched on 23 November 2016 in Brussels, during the Conference Inclusive Smart Cities: A European Manifesto on Citizen Engagement, the EIP-SCC Manifesto on Citizen Engagement, an official declaration of the Cluster’s commitment to promote the engagement of citizens in the design and co-creation of Smart Cities.

The Manifesto was the outcome of a co-creation experiment, carried out over one year, that has seen more than 50 stakeholders, representing different sectors of the economy, engaged and actively contributing to shape its contents. The primary goal of the Manifesto is to foster knowledge sharing of best practices and collaboration on the co-creation of models that use innovative solutions for ameliorating the civil society, with a particular focus on the engagement of weaker and excluded categories.

In so doing, it calls for commitment towards the improvement of the quality of life by tailoring city measures on citizens’ needs. In particular, by outlining its principles, the declaration urges cities to adopt inclusion policies, to educate both city officers and citizens on this matter, to set up collaborative models, to enhance digital literacy, to promote open science and open data as well as to seek co-operation with other cities to strengthen the Smart Cities Network.

To date, the Manifesto has been endorsed by more than 130 private and public sector representatives, reaching multiple European and international stakeholders. To ensure a wider geographical and, thus, language coverage of the Manifesto, various translations of the document have been made available. The so-called ‘Manifesto goes local’ campaign, currently ongoing, is facilitating the dissemination of citizen engagement principles also in areas where English is not widely used.

Aiming at having an increasing number of cities endorsing the Manifesto, implementing and, consequently, promoting its principles, with the ultimate goal of making smart cities more inclusive, the Action Cluster has started the assessment of the Manifesto’s principles implementation. The analysis, conducted via interviews and an online survey, aims at finding citizen engagement’s best practices, solutions and collaborative models to be disseminated and replicated on a larger scale. In particular, data and information are gathered around the six main domains characterising the Manifesto. Results of the analysis can offer examples of obstacles and solutions, showcasing for each of the above mentioned domains, practical examples. Outstanding cities, upon the evaluation, will be nominated ‘Ambassadors’ and will contribute to the dissemination of the Manifesto principles, while participating to peer-learning and other knowledge sharing exercises.

Technical and financial readiness checks

Project are assessed on the basis of two main criteria, the technical readiness and the financial readiness. The project associated with the application must be well advanced in technical terms (design, approvals, permits, consultation, interfaces, procurement, etc.) and financial terms (business case development, availability of funding-affordability, availability of private sector financing and commitment of the latter in terms of achieving financial close within the timescales set in the call, etc.).

Key matters considered by banks/investors when financing a project

The following list include due diligence items that a lender may consider when assessing a project for lending purposes. Please bear in mind that this list is not exhaustive and only indicative, as different banks/investors have different approaches to project appraisal.

- Demand/needs analysis supporting the project decision

- Option analysis and a good quality Cost-Benefit Analysis based on realistic data and forecast

- Relationship of the project with the existing infrastructure and impact of the former on the existing sector (transport/energy) system

- Medium-term investment plan and business case to support and justify the project and/or the replacement strategy of previous fleets or infrastructures. The basis should be the transport/energy needs of the reference area in the city, in conjunction with operators’ organisation and structure for Operation and Maintenance and with the overall city mobility/energy organisation and policy.

- Technical feasibility, status of design development, proven quality of the assessment of project costs (whole life project costs approach)

- Strength of the political support to the project, especially in terms of affordability and funding

- Financial analysis of the project and its impact on public budget

- Status in terms of Environmental Impact Assessment, required studies and their approvals, stakeholder consultation/approvals, administrative/statutory approvals (including at city masterplan level) and all project interfaces

- Clear project structure (who does what) including risk allocation (who takes what risk), in terms of project preparation, procurement, construction, operations, revenue risk, repayment of the loan, and so forth (the list of project risks is much more extensive, this are just an example)

- Status of the procurement process and procurement strategy for the delivery of the project

- Clear identification of the funding and financing structure, including identification of the borrower

- Credit risk assessment of the borrower and/or guarantor associated with the loan

EXAMPLE

In March 2015, the “Smart Cities & Sustainable Development” programme developed by the EIB and Belfius Bank aims to assist and provide financial support for towns and cities – including the smallest ones – for their sustainable mobility, urban development and energy efficiency projects. Belgian local authorities have been the first in Europe, starting in June 2014, to benefit from preferential rate loans for implementing their "Smart Cities" projects. With 400 milions available, Nine months later the progress has been excellent: the first loans, totalling EUR 35m for eight concrete projects in Belgium, have been approved

Belfius Bank requires the Promoter to ensure that contracts for the implementation of the project have been/shall be tendered in accordance with the relevant applicable EU procurement legislation (Dir. 2004/18/EC or 2004/17/EC and Dir. 2007/66/EC [amending Directives 1989/665/EEC and 1992/13/EEC]), with publication of tender notices in the EU Official Journal, as and where required. In some cases schemes may be developed by private entities which are not subject to the EU procurement directives.