TO DO 1: SET MILESTONES AND TARGETS

and agree on responsibilities, who does what

The first TO DO is to define milestones and concrete, effective targets for the strategy and/or policies per objective from the DECIDE & COMMIT stage. Subsequently, within the city’s administration and the wider stakeholder network, a division or roles has to be arranged, making specific departments or staff positions responsible for achieving particular milestones and targets (“Who does what”). This is usually done by internal meetings and workshops, and informal consultation with stakeholders.

WHY?

This TO DO helps to work in an efficient, effective, and SMART way towards execution of the strategies and/or policies as prepared in the plan. SMART as defined in management, meaning Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-bound (see O’Neil and Conzemius, 2006). In addition, it is needed to avoid confusion over who has (final) responsibility for achieving the agreed milestones and targets.

TO DO 2: EXPLORE STATE-OF-THE-ART OF RELEVANT AND APPLICABLE METHODS AND TECHNOLOGIES

internal and external

The second TO DO is to explore, make overviews of, and study the state-of-the-art in relevant methods and technologies, which might be contemplated for the action plan. These methods and technologies must be assessed on their appropriateness for the local situation in terms of densities, building or infrastructure characteristics, mobility patterns, legislative context, and so forth. Specific preconditions for contemplated solutions need to be checked as well, for example with respect to GDPR. This can be done by the city administration itself, if competences are present, by internal and external pre-consultation of experts, engineers, consultants, research organisations on technologies and methods the city wants to deploy.

EXAMPLE: CO-OPERATION WITH LOCAL RESEARCHERS ON ASSESSMENT OF DEMONSTRATED SMART CITY SOLUTIONS FOR FELLOW CITY BRNO

Brno asked its RUGGEDISED project partner - SIX Research Centre from Brno University of Technology - to deliver expert analyses on six concrete topics related to smart urban development: smart thermal grids, smart power grids and e-mobilty, ICT, safety and security, smart waste management, sharing economy, and mobility. Each analysis describes solutions currently demonstrated, mostly in RUGGEDISED lighthouse projects, and summarises relevant worldwide and European trends. The analysis also makes specific recommendations of best practices for the Brno city, in particular for its replication of the area within Špitálka district. These expert analyses will serve as the basis for planning and designing a new smart city district in Brno. SIX Research Centre will follow up on these studies with co-ordination and organisation of expert roundtable discussions in the second half of 2019. The results from these roundtable discussions will help the city administration of Brno to proceed with specification of which concrete smart solutions will be used in future site development. Nevertheless, this is only a small part of Brno’s co-operation with partners from the local academic sector. There is a lively co-operation based on projects like JRGL, Brno Ph.D. Talent on the academic capacity building and many others. The development of the programme Smart City Vouchers, dealing with the new ways of Pro-innovation Public Procurement are now in the preparation phase (City of Brno, 2019).

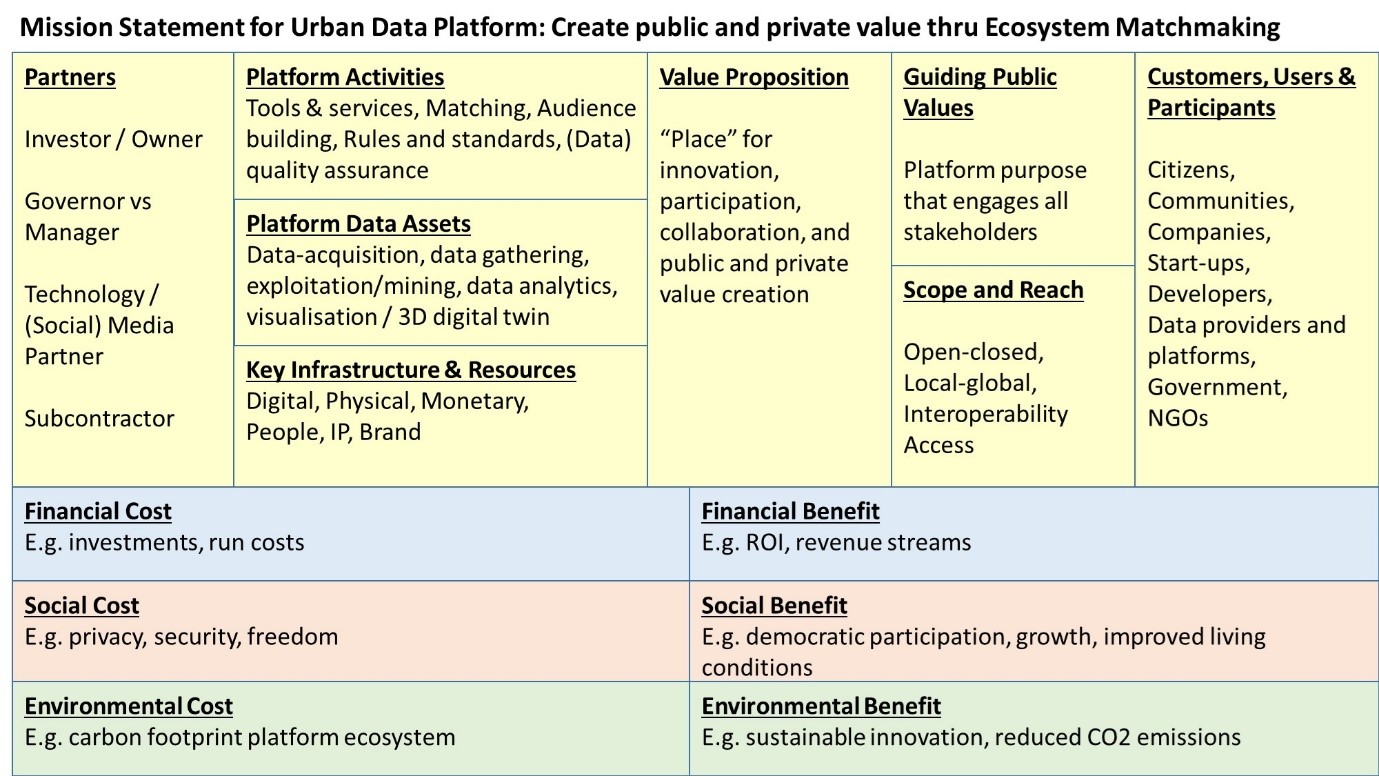

EXAMPLE: URBAN DATA PLATFORM BUSINESS MODEL CANVAS

Many cities struggle with progressing their platforms beyond Open Data platforms. They also struggle to engage with the private sector, especially because it is not easy to make a business case for a platform of which the value growth over time is not yet predictable. The Urban Data Platform (UDP) Canvass helps policy makers to take a long-term and comprehensive view on how to use data in their city, and how to foster (societal) innovation and citizen engagement. The UDP Business Model Canvass has been developed specifically for the design of Urban Data Platform initiatives. It combines a triple bottom line with business model elements that drive sustainable/societal business models. Triple bottom line refers to the fact that an UDP does not only have financial costs and benefits, but also social and environmental costs and benefits. Elements that capture the platform and societal nature of an UDP are “Leading Public Values” (NB not value), “Scope and Reach” and “Platform Data Assets”. The cities in Horizon2020 SCC-01 Ruggedised project are applying this instrument, for example for assessing district heating refurbishment in Glasgow.

The UDP Business Model Canvass has been developed from the position that government should take the lead in the development, management and ownership of Urban Data Platforms, as governments mostly do in case of vital infrastructures. As a planning tool it helps policy makers to take a long-term and comprehensive view on how to use data in their city, and how to foster (societal) innovation and citizen engagement. The Urban Data Platform Business Model Canvass helps city officials to make an informed decision on why and how to take the lead in the development, ownership and management of UPDs and how to engage with stakeholders in their city ecosystem (Erasmus University et al., 2019).

WHY?

This step provides an orientation on how to achieve the proposed milestones and targets practically seen by exploring the suitability and applicability of different methods and technologies. Besides, having an overview of which solutions could be part of the plan, supports a transparent discussion with local stakeholders on the pros and cons of choices later at the PLAN stage.

TO DO 3: RECONNECT TO STAKEHOLDERS

communication and consultation on envisaged actions

After the exploration of suitable methods and technologies in the previous TO DO, the next step is to actively continue and renew the communication with the key stakeholders. The purpose of these meetings and workshops is not only to hear the opinion of the key stakeholders on the outcomes of the exploration of possible solutions of the key stakeholders, but also to start a dialogue about which solutions would suit the stakeholders’ interests.

Normally stakeholders have already been engaged for specific TO DO’s in earlier stages, however, as the “routes” prioritised earlier become more narrowly defined and worked out in more detail into actions, it is of utmost importance to keep the stakeholders engaged and (re)connect with them on a regular basis. A mistake made often, is to engage stakeholders at the start of the preparation of plans, but not anymore at a later stage, what might lead to a less positive attitude towards the plan.

City administrations should consult all local stakeholders, including citizens and local businesses, in a proper way by keeping in mind that:

- Stakeholders might not be aware of specific issues deemed important by the city administration, or might have other priorities

Energy efficiency might not be the main concern of stakeholders and users of buildings and urban infrastructure, however, expected savings on energy costs are often an important motivation for agreement to plans for smart city and low energy district projects. For example, when buildings are refurbished to increase their energy efficiency, savings on the energy bill with the added benefits of more indoor comfort and a better condition of the building, are an important motive to consent to the proposed actions (R2Cities, 2014).

Motivation is also important for later use of the refurbished buildings, infrastructures or new services. For example, Yoldi (2017) stresses that user behaviour is a key issue for the eventual result of energy efficient buildings, because if end users are not willing or being able to use the technologies properly, this will lead to lower energy performance values. Communication, raising awareness and the training of the tenants or other users is considered as probably the most important factor to success.

Realising that stakeholders might have different priorities than energy efficiency of their building, means that city administrations should also develop a specific approach towards households suffering from energy poverty or increased costs of clean mobility as part of the plan.

- Win-win situations must be created by including other benefits from the envisaged actions than savings and reduction of GHG emission in the plan, such as less air pollution, or enlarging the scope of the envisaged actions, such as better quality of the public space;

For instance, the narrative of energy efficiency investments should include those attributes that the homeowner is likely to value, and be tailored in order to emphasize the direct co-benefits of the measures – including a higher living standard, increased comfort, improved aesthetics, enhanced lighting quality, healthier ventilation, and better acoustics, among others (City-zen, 2016; EASEE, 2012; Ferreira et al. 2015). Or, as one of the interviewed key players in the field of smart cities put it, "To engage with citizens, you need a compelling argument - not just what you do, but how you do it. You need to create a dialogue and answer the question: what's in it for me?".

As “co-benefit” refers to any positive impact or effect that exceeds the primary policy or project goal, regardless if intentional or not. Communicating the broad range of expected co-benefits creates a positive attitude and makes it possible to include the wishes and hopes of many stakeholders, including those who are sceptical about climate-energy issues (Bisello and Vettorato, 2018).

- Allow some flexibility to adjust the potential solutions and envisaged actions;

As stakeholders might have different preferences, there should be sufficient room for adjustment of the plan to stakeholders’ preferences.

- Create joint ownership of the plan

One interviewee explicitly mentions that a top-down approach should be avoided as it does not create joint ownership of the plan: "One important point is that I would rather not start a top-down initiative but I would take the people along before - maybe at the same time. So citizen participation helps to create ownership for the project, to make what’s possibly visible - why is a smart city useful to them - it's not just technological gadgets but it is supporting their quality of life " (Interviewee #5, 2017).

EXAMPLE: CREATE OWNERSHIP DURING THE PLANNING PHASE

"Co-operation with the homeowners and tenants to tailor the energy efficiency solutions to suit their requirements has been recognised in the EU-GUGLE project in order to best meet the ambitious sustainability goals. The involvement of the occupants during the planning and post-occupancy stages gives each person involved a greater sense of belonging and motivation to meet the collective goal of energy savings by adapting their own behaviour" (Morishita, 2017).

EXAMPLE: OPINION IN SOCIAL CIRCLES MATTERS DURING DEMONSTRATION

People tend to trust the opinions of their social circle as well as their own direct experiences, and demonstration projects provide one way to influence these factors (HERON, 2016a). Demonstration projects and living labs can involve the public and allow them to develop their own awareness and motivations based on their own direct experiences, or those of their social circle, instead of words and papers.

EXAMPLE: PRE-REFURBISHMENT SURVEY ON ENERGY BEHAVIOUR

In the Bolzano demo case of SINFONIA project a pre-refurbishment survey was conducted in order to better understand tenants’ current energy consumption behaviour in social housing, and how this influenced the performance of the chosen technologies, for example by inefficient, but more short-term rewarding, behaviour. A reaction strategy would be installing a monitor displaying information on aggregate future benefits from ventilating efficiently, or about what others do (DellaValle et al., 2018).

ADRIANO BISELLO, SENIOR RESEARCHER, INSTITUTE FOR RENEWABLE ENERGY EURAC

Like other collaborative group discussions, the World Café method wants to create a communicative space for sharing and developing collective knowledge, but the World Café method is less formal as the usual focus group discussion. People like to discuss with some food or having a drink in the hand, the atmosphere is good, the results more spontaneous. In the focus group, each participant tends to represent the institution, more than his/her personal point of view, in this way some “ideas” may not be expressed in the focus group. To assess group knowledge and group thinking about complex topics, as the co-benefits of smart city plans, it is vital to create an atmosphere of trust, purpose and open discussions.

Like other collaborative group discussions, the World Café method wants to create a communicative space for sharing and developing collective knowledge, but the World Café method is less formal as the usual focus group discussion. People like to discuss with some food or having a drink in the hand, the atmosphere is good, the results more spontaneous. In the focus group, each participant tends to represent the institution, more than his/her personal point of view, in this way some “ideas” may not be expressed in the focus group. To assess group knowledge and group thinking about complex topics, as the co-benefits of smart city plans, it is vital to create an atmosphere of trust, purpose and open discussions.

WHY?

The buy-in of stakeholders, as owners and users of the built environment, is essential for the successful preparation and implementation of any smart city or low energy district plan. They must approve, co-design, and frequently co-realise the plan, and will feel the impact of the proposed changes.

Regarding awareness and motivation of stakeholders, the decision of whether or not to invest in smarter solutions and plans for low energy districts, is driven by many factors besides economic reasons. More factors are in play, other than simply cost reduction. Energy efficiency is often a minor factor, with a "low priority, simply because households (even the environmentally aware ones) are much more attracted to other attributes of the products (be it dwellings or vehicles), such as thermal, visual and acoustic comfort, aesthetics, health and safety " (City-zen, 2016b; HERON 2016a). In interviews of homebuyers, none of the owners had considered energy use in their purchasing decisions, while those customers that had installed efficiency measures stated that both thermal comfort and aesthetics were important drivers in addition to reduced costs (EASEE 2012; Tuominen et al., 2011). "Energy is regarded more as a public service than a valuable resource, which is difficult to change unless this implies a tangible improvement in the standard living " (BEEM-UP, 2014).

Motivation is also fed by the source of information - and the trust involved: "Even the best advice of the most competent professional will not be accepted, if it is not corroborated by the opinions and experiences of relatives, friends, [or] colleagues" (HERON, 2016a).

The abstractness of concepts such as sustainability and energy efficiency, may also hinder awareness and motivation for such plans. Research by Mörn et al. (2016) found that the engagement of residential tenants and their interest in visualised individual energy data for their households, depended upon how much information was presented and if this was easily understandable: “It could, for example, be difficult for many people to relate to individual kWh figures to understand the impact of their energy behaviour. Possibly, a larger focus on which effect the energy savings have on consecutive fossil fuel savings, or that certain savings correspond to 10 avoided hot showers or one avoided 10-mile car drive, could alter the tenants’ energy behaviour more".

Lastly, stakeholders often have to co-finance specific investments. Lack of awareness or motivation might preclude private investments in solutions for smart cities and low energy districts, especially when proposed solutions are insufficiently aligned with their respective interests. Including co-benefits in the plan, plays a central role in overcoming this barrier.

TO DO 4: VISUALISE LOCAL CHALLENGES AND POTENTIAL IMPACT

of prospective methods and technologies in neighbourhoods

After consultation with the stakeholders, the next TO DO is to include more spatial details in the envisaged actions in terms of neighbourhoods or building blocks, by making a geographical refinement of the specific challenges identified in the VISION stage. What is more, the potential impact of actions must be shown with the help of dashboards, urban platforms, etc. Such tools, for example based on Building Information Models (BIM) or Geographical Information Systems (GIS), can visualise specific local challenges and the potential impact at neighbourhood level. Information about the impact of contemplated solutions, might influence the choices to be made in the next TO DO. ICT tools showing the state of the current built environment with its energy and transport infrastructures, and analysing the suitability of various smart city solutions for specific areas, can help to develop a “common operational picture” and prepare for collective agreement later.

EXAMPLE: COLOUREE

The Colouree platform is an example of software as a service, supporting the real estate market by making use of enhanced geo-referred data and urban spatial analysis with the aim of providing a deep understanding about locations and neighbourhoods. It allows its users to easily match their needs in term of lifestyle, business or commute, with the right location and surroundings. It enables to select the properties and places of interest directly on a web-based map; to discover the most highly rated properties and locations for end users needs and interests; to compare buildings taking into account various indicators and to obtain the real-time results of the analysis of almost one million measurements and geo-referred data in about three minutes. This tool has been successfully used in the Milan Metropolitan area within the European Natural based solutions project Nature4cities by contributing in defining a a system of integrated multi-scale and multi-thematic performance indicators for the assessment of urban challenges and nature-based solutions (Nature4Cities, 2019).

WHY?

The aims of this TO DO are to gain an in-depth understanding of the local situation, and to create critical mass regarding contemplated solutions. These BIM/GIS based analyses provide insight into what to do where.

JAROSLAV KACER, CHAIRMAN OF COMMISSION OF BRNO CITY COUNCIL FOR OPEN AND SMART CITY – FORMER DEPUTY MAYOR CITY OF BRNO

”To expect, that new smart devices or technologies make a city „smart“ is unwise. The important part is to put your innovation into the local context and modularly build your city. Try to imagine your smart city as a cyber-physical building set, that can be expanded or adapted based on current needs.”

”To expect, that new smart devices or technologies make a city „smart“ is unwise. The important part is to put your innovation into the local context and modularly build your city. Try to imagine your smart city as a cyber-physical building set, that can be expanded or adapted based on current needs.”

TO DO 5: DRAFT A LIST OF RELEVANT ON-GOING AND POSSIBLE NEW PROJECTS

with stakeholders

With more information what can be done where, the next TO DO is to create a comprehensive list of relevant on-going and possible new projects in transport, energy efficiency and RES, infrastructures and ICT, for instance, as included in the Sustainable Energy and Climate Actions Plans developed under the Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy. This is done together with the stakeholders. Plans are becoming rather concrete at this stage.

EXAMPLE: USING PROVIDERS’ EXPERIENCES FOR SHAPING INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS BY PROCUREMENT

Cities can be driving forces behind innovations but being up to date in all current technologies can be a very big challenge. With a new innovative procurement method, it becomes possible for cities to benefit from extensive experiences providers in highly innovative areas already have. At the same time the providers get the chance for new business opportunities as well as the chance to test their innovative ideas under real-life conditions. This can be a big asset for them in the further development of their products. A classic win-win situation.

In connection with fitting smart functionality into lampposts for Smarter Together, the City of Munich has been experimenting with an individually designed project-specific procurement instrument called "open calls" since autumn 2017. For the implementation a close cooperation with local regulatory and procurement experts is crucial. Rather than asking for specific functions, open calls inspire innovation on the part of providers. They are challenged to develop solutions taking into account the requested services on the one hand while also contributing ideas of their own.

The reason behind this new approach is the fact that there is need for relevant end-to-end solutions. This new type of procurement allows Smarter Together and thus the City of Munich to benefit from the extensive experience of the providers in highly innovative areas in return for a minimal investment risk. The open calls were addressed to start-ups, researchers and developers, but also established corporate players.

The first open call for the lamppost sensors was concerning weather data and air quality. The cooperation with the chosen providers started in spring 2018. The second open call was about traffic counting and parking space detection. The implementation of the solutions started in early 2019.

In both cases the ideas brought forward by the providers were a valuable contribution to the Smarter Together project. The lamppost solutions have been implemented together with established technology companies as well as local start-ups (City of Munich, 2019).

WHY?

When planning new roadmaps with targets, consistent with the strategies set in place in the DECIDE & COMMIT stage, collecting on going or already planned projects is key for optimising the resources and selecting the most appropriate options.

Indeed, the integrated approach – or cross sectorial approach – needs a complete overview of on-going/planned projects, in order to make the right decisions. Especially keeping a permanent holistic view on the different projects in different sectors, will contribute to an optimised alignment of the timelines, that will lead to saving time, money and resources, as well as ensuring the appropriate design/characteristics of future equipment/systems.

A few typical examples:

- Developing new roads/streets and integrating other equipment when digging the ground (i.e. installing fiber optics, water supply pipes, district heating grid, gas distribution, electricity supply);

- Implementing a district heating/cooling grid and anticipating future retrofit of existing buildings (improving energy efficiency) and/or extension of the built zones, and/or installing solar thermal equipment on all buildings for hot water supply for instance, that will impact on the design and operational characteristics of the district heating equipment;

- Developing pedestrian zones and bicycle lanes in the city center, anticipating future mobility schemes (i.e. tramways, no traffic in city center, new shared/green squares).

TO DO 6: ELABORATE COSTS AND RISK MITIGATION, CHOOSE FINANCIAL SCHEMES AND SOURCES

by financial readiness checks and financial model(s)

In the DECIDE & COMMIT stage, exploration of the possibilities and conditions of different financial schemes have already taken place. Now, this TO DO focuses on making final choices for the financial models during implementation of the plan. Different groups of activities are part of this.

Firstly, a detailed elaboration of costs and yields needs to be created for the projects on the list resulting from the previous TO DO. This means calculating key financial parameters such as capital expenditures (CAPEX), operational expenditures (OPEX), return on investment (ROI), profitability and so forth.

Many solutions for smart cities and low energy districts, have high initial costs and a questionable profitability. Cities' and investors' initial perception is of prohibitively high costs, whether upfront costs, initial costs, or overall costs, are a common issue facing projects at different stages of development and implementation. Factors affecting this perception include the methodologies for determining return on investment (ROI), including internal and external rate of return, as well as assumptions about interest and discount rates. Different ways to deal with high costs are:

- Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can often help overcome other challenges facing smart city projects, including lack of initial funding, lack of staff capacity, lack of technical capacity to develop and manage innovative projects. The PPP may transfer to the private sector a large share of the responsibility for developing, managing, and completing the project. But the private sector may only be willing to engage in a PPP if the "partnership structure assures a competitive rate of return compared with the financial rate of return they could get from alternative projects of comparable risk" (Stacey et al., 2016c);

- Bundling highly profitable project investments with less profitable or unprofitable elements can be a method for expanding the project while retaining profitability;

- Mixed financing from various sources and types of investors, and innovative business models where operational cost savings finance higher investments, or a longer time horizon for return on investment is accepted because of other advantages;

- Revolving funds, green bonds, crowd funding, pre-financing and subsidies;

- Sustainable procurement including environmental externalities. By monetarising environmental disadvantages of fossil energy use, sustainable projects are higher valued.

However, also citizen stakeholders may have a perception of prohibitively high investment costs and prohibitively long payback times as a common issue facing projects where citizens co-finance the investments. This is often related to their socio-economic status and access to capital, motivation, problems organizing collective agreement and action, and lack of awareness of financing opportunities. Apart from stressing the direct co-benefits of the plan (Ferreira et al., 2015), the timing of investments can also provide an opportunity for less costly investments with shorter payback times. For instance, timing the integration of smarter technologies to replace an existing intervention (e.g. substituting PV roof tiles instead of normal planned roof replacement) to reduce additional costs can help alleviate some of the financial burden (R2CITIES, 2014). Usually, the “price” and the “location” are the most important criteria in the choice of a residential property when renting or buying, while the energy efficiency of the building and the energy costs, are considered of minor importance. Real Estate Agents tend to underestimate the role of energy efficiency as a factor in the total price, and attribute the higher value of a new property entirely to its newness. Possibly, this is the result of their extensive experience with trading existing properties, which have usually poorer energy efficiency. However, more and more studies at European level depict an emerging market for high-energy performance buildings, gaining a price premium, ceteris paribus, near 5 to 10% compared to low class rated properties, although this differs between the rental and selling market (Pascuas et al., 2017).

Secondly, this information is used to assess the suitability of possible financial schemes. This entails also a proposal for sources of finance and funding. A wide range of possibilities from within financial and funding schemes exists, see section 2.3. A financial readiness check can be instrumental to prepare requests for funding (see 3.3 Inspiration). Split incentives are a commonly encountered issue in smart city and low energy district projects, which is partly related to sources of finance (see Bird et al., 2012). It means that the actors financing the project, often a real estate developer or building owner, and the actors benefiting from the project, usually the tenants, are different. For these reasons, a fair division of costs and benefits must be part of the plan. It can be achieved by users contributing to the costs of the investment, ESCO’s, mixed financing business cases, sharing of profits according to investment, or energy-neutral rents (consisting of rent and energy costs together, where energy savings finance the refurbishment of the buildings).

Lastly, finance and funding organisations will ask for more information about the real and perceived risks associated with the projects on the list. Generally speaking, conventional solutions are often preferred by stakeholders in order to avoid unknown problems with innovative solutions, such as flaws in construction work or inadequate maintenance (HERON, 2016a). New or innovative solutions are considered to carry with them a higher implicit risk, and this leads to apprehension from many stakeholders, including public entities, private enterprise, the public, and financial lenders. Small-scale projects can provide a low-risk way for public entities to support test-beds for innovation; raise familiarity and skill levels by involving local partners in the project; reduce apprehension by verifying and validating the project claims; and alleviate unfamiliarity through public exposure and participation. Other ways to deal with innovative solutions perceived as too risky, are organising a better exchange of knowledge, and a a better integration of technological and financial economic knowledge e.g. investors and solutions providers. Ideally, possible risks should be roughly identified before negotiations with the preferred sources of finance and funding can start. Risk mitigation, contingency planning, and guarantees on performance of smart city and low energy district solutions help to make the envisaged solutions less risky.

In the end, this TO DO results in a choice for a financial model, i.e. a revolving fund, loan, grant, or mixed financing, and a (sub)plan for mitigating risks.

EXAMPLE: MIXING HIGHLY PROFITABLE WITH LESS PROFITABLE INVESTMENTS

"…building pools - can provide a good solution for the management of property energy issues. The technique involves combining several buildings into a single joint project. This allows elements with lower energy saving potential to be included with others having higher energy saving potential. These pooled buildings have different levels of energy consumption, different construction materials, different fixtures and fittings etc., which leads to profitable cross calculations and also means that seemingly unprofitable buildings can be integrated into the project" (CITYnvest, 2017).

EXAMPLE: PILOTS TAKE AWAY PERCEPTION OF INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS AS TOO RISKY

"… in a big organisation like our city … change is difficult. It is difficult to say "let's do it in this way instead of how we've always done it" - that is difficult to implement. But if you do pilots, and you try something instead, and everyone sees that it works out well, then it is very inspiring for others to just start following. So pilots are important for inducing change in a big organisation...there are no big dangers since they are still rather small, but once they have been implemented, they are like lighthouses and lead the way" (Interviewee #6, 2017).

WHY?

Projects focusing on issues such as building refurbishment for higher energy efficiency, are often not considered as sufficiently economically attractive for investors.

One of the causes for this is the fact that the social and environmental costs of energy use are not included in the price. This reduces the value of saved energy, while increasing the relative price of renewables compared to conventional sources (R2CITIES, 2014), making it difficult to classify energy-saving measures within the standard financial models and valuation procedures used in finance (City-zen, 2016).

Energy saving aspirations may provide net benefits to the city or the community, but will likely add costs that are difficult to finance through conventional mechanisms that do not value non-monetary benefits (Stacey et al., 2016a). In short, "the payback period for companies is too long and the risk too high" (Rivada et al., 2016). For citizens, this payback time may not be an issue from a true economic viewpoint - if the net present value over the lifetime of the investment exceeds the investment cost – but the lifetime of the investment may exceed the expected occupancy time of the homeowner. In this case the homeowner may move before their investment is recovered, and the selling price may not be expected to properly reflect the investment (EFFESUS, 2017). There may also be a perceived (or actual) negative effect on the value of a property due to project intervention (Di Nucci et al., 2010). This can include value or appraisal based on architectural features, such as the covering of external brick features due to the application of external insulation (and then stucco, paint, or another "lower value" covering).

Regarding split incentives, they reduce the attractiveness for the Real Estate Developer or landlord of a prospective investment in a project or smart, energy-efficient solutions which do not provide many financial benefits (HERON, 2016b; City-zen, 2016; Rivada et al. 2016). Legislative frameworks play a role as well in this: In some cases the building owner is not allowed to reflect the investment in the rental price, and thus has no way to recoup the investment. In other cases, bilateral contracts can "easily arrange the transfer of money, [but] they do not solve the transfer of risks" (City-zen, 2016a).

New or innovative solutions are generally unproven and unfamiliar, and often considered to incorporate more implicit risk. This risk can manifest itself in apprehension from public entities to support innovative projects, hesitation from private enterprises to get involved in projects where they lack experience, unwillingness for public consumers (end-users) to support unproven projects, and increased costs (or outright refusal) for funders to back innovative projects. Innovative processes are inherently unproven and generally do involve increased risk of failure; especially compared to the existing approach or business as usual.

Public entities have several concerns, including fear of making a bad decision with public money and fears owing to lack of clear knowledge on costs and benefits, lack of experience combined with risk-aversion, fears owing to lack of clear knowledge on costs and benefits, and the fear of unforeseen or long-term risks emerging after project conclusion, which may trigger a loss of confidence and backlash against innovative projects (Rivada et al., 2016; EASEE, 2012). Private enterprise, including private partners in PPP, cite the public lack of demand and lack of internal awareness (esp. among architects and engineers) of innovative solutions (Rivada et al., 2016; EASEE, 2012). With respect to public consumers, the public may be reluctant to adopt, convert to, or invest in more innovative solutions due to scepticism, unfamiliarity, expectations of unpredictability, and concern over the reliability of new technologies (HERON, 2016a; MEnS, 2015; BEEM-UP, 2014). They may also lack willingness to try new things, or be comfortable in their routines and unwilling to behave differently or have to learn new skills. Regarding financial lenders: With the increased risks come increasing costs, and an increasing difficulty to secure funding. Much of this is due to the larger uncertainty inherent to the approach, leading to difficulty in properly characterising the financial situation within an acceptable range of certainty. Banks may be unwilling to finance innovative projects due to lack of knowledge and lack of experience" (Rivada et al., 2016; EASEE, 2012; BEEM-UP, 2014).

TO DO 7: RANK AND SHORT-LIST PROJECTS

according to their viability and select the best projects

Now the financial for the envisaged projects is clear, the next TO DO is to reach agreement with the key stakeholders about which projects should be short-listed. In meetings and workshops with stakeholders, proposed projects on the list drafted for TO DO 5 have to be ranked according to their viability. Comparable to the DECIDE & COMMIT stage, where “routes” to solve the problems where prioritised, this is done by taking into account factors such as:

- Maturity of the proposed project;

- Financial feasibility;

- Risks (not only financial, also other ones);

- Potential impact;

- Consistency with targets in general, overall city plan or vision.

After the ranking, the most viable projects must be selected. Usually, a couple of iterations is needed to come to an agreement about which proposed projects should be selected. Co-design of the content of plans with other stakeholders, often in a couple of iterations, contributes to establishing the basis for collective agreement.

EXAMPLE: COLLABORATION ON SMART CITIES IN THE QUADRUPLE HELIX

Fomento San Sebastian is leading the transition of the Txomin neighbourhood in the Urumea Riverside District to a smart district, branding on sustainability. San Sebastian started planning the process in the FP7 STEEP project with the definition of strategic projects and the involvement of the smart ecosystem of the city. The Smart Plan for the city was designed, in which an integral plan for the city’s smart strategy was established with the main challenge of establishing a strategic line with shared objectives and to give coherence and co-ordination to the public action. Fomento San Sebastian works on a smart clustering policy that involves the stakeholders of the smart environment of the city in the different actions and projects developed. Replicate project funded by the H2020 programme and coordinated by Fomento San Sebastian has deployed implementations in energy efficiency, sustainable mobility and ICT/Infrastructures in the city.

The Txomin residential neighbourhood has the Urumea river that crosses the district, acting as the main axis of the area but also representing a barrier, as well as being the cause of the area’s flooding problems. This area was urbanised during the first half of the 20th century, with low energy efficiency buildings, connection problems etc. To address this problem, the City Council defined different plans that, together with the smart projects that are under way, are making possible the transition to a smart district. In the Replicate project framework 156 homes and 34 commercial premises are being retrofitted, the District heating system will give service to the 1.500 new homes and the 156 retrofitted properties. A demand management platform is being developed which will enable users discover their energy consumption in real time. Actions implemented in sustainable mobility include electric buses for the connection with the city centre and electric vehicles (e-cars and e-mopeds) as well as a Smart Mobility Platform. In the field of ICTs, the city’s high-speed mobile wireless network, smart public lighting and the Smart City Platform have been developed. This platform enables part of this information to be published in Open Data and additionally allows for a Citizen Participation platform that has been launched.

Replicate and other complementary smart city projects led by Fomento San Sebastian are fostering the transformation of the Txomin neighborhood that will allow validation of different solutions for their replication in other districts and cities around Europe.

EXAMPLE: PRIORITISING ACTIONS FOR A SECAP

The Joint Research Centre published a guidebook which explains how to put in place and implement a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP) (JRC, 2018).

A baseline review is the starting point for the SECAP process from which it is possible to move to relevant objective-setting, elaboration of adequate Action Plan and monitoring. The baseline review needs to be based on existing data. It should map relevant legislations, existing policies, plans, instruments and all departments/stakeholders involved. Completing a baseline review requires adequate resources, in order to allow the data sets to be collated and reviewed. This assessment allows elaborating a SECAP that is suited to address locally important issues and specific needs of the local authority’s current situation. The aspects to be covered can be either quantitative (development of energy consumption...) or qualitative (energy management, implementation of measures, awareness...). The baseline review allows prioritising actions and then to monitor the effects based on relevant indicators.

The main questions that guide the process are the following: What is the energy consumption and CO2 emissions of the different sectors and actors present in the territory of the local authority and what are the trends? Who produces energy and how much? Which are the most important sources of energy? What are the drivers that influence energy consumption? What are the impacts associated with energy consumption in the city (air pollution, traffic congestion ...)? What efforts have already been made in terms of energy management and what results have they produced? Which barriers need to be removed? What is the degree of awareness of officials, citizens and other stakeholders in terms of energy conservation and climate protection?

After the baseline data collection and the CO2 baseline emission inventory compilation, a list of projects within the public administration on energy infrastructures, municipal fleet, buildings, energy consumption and energy management, transport and mobility must be identified. In addition, the potential projects where the private sector and industry can contribute to achieving the common objectives should be charted. The prioritisation of projects to implement depends on the expected impact that the project has in term of CO2 reduction, the financial resources available both from the public and private sector and the maturity and expected feasibility of the projects.

WHY?

A choice must be made from projects which are the most viable, and at the same time, will have the highest impact, in order to achieve the objectives as stated in the VISION stage.

TO DO 8: ENSURE APPROVAL AND COMMITMENT

for selected projects by city administration and stakeholders

After the best and most satisfactory project proposals have been selected, this choice must be approved by the politicians in the city administration, while key stakeholders should support this selection as well. They must approve the proposed projects and commit themselves to their realisation in future. This buy-in of the city administration and the key stakeholders, helps to secure budgets and human resources for realisation later.

As mentioned earlier, in the field of smart cities and low energy districts, a common situation is fragmentation among a large number of different actors and a "lack of co-ordination/co-operation between multiple stakeholders and their interests" (Rivada et al., 2016). This situation is most commonly encountered in projects that involve renovation or retrofitting of multi-ownership buildings. In many countries, property owners within residential multiple ownership properties commonly (or are legally required to) establish an owners' association, condominium agreement, or housing cooperative to manage common building maintenance and utilities (EFFESUS, 2017; LEAF 2016). As part of these systems, owners generally make monthly or annual payments into a communal fund (and have a collective debt), to pay the costs of regular building maintenance, and cover unforeseen or future repairs. Existing management and funding systems also provide a vehicle for the organisation of collective action and for collective investments in smart city projects, such as energy efficiency and performance improvements. In the absence of an existing collective agreement, professional property management companies can also fill the gap and "be used as an organisational and financial vehicle for energy-related retrofits in the absence of building owners’ associations" (EFFESUS, 2017).

Organising collective agreements among the distributed owners and different actors in multi-owner buildings adds an additional layer of complexity to an already comprehensive process, owing to the diversity and divergent interests of the stakeholders (EASEE, 2012; EFFESUS, 2017). This challenge is often intertwined with the split-incentives issue, as "…owners are rarely a homogeneous group, but a mix of owner-occupiers and short- and long-lease landlords, and of different age groups and household forms" with "often different and opposing interests on how to develop their properties" (EFFESUS, 2017).

ETIENNE VIGNALI, PROJECT MANAGER LYON CONFLUENCE

Thanks to the Smarter Together project, the Lyon-Confluence urban project cooperates with a broad range of (public and private) stakeholders, to make progress on energy challenges faced by urban areas.

WHY?

This TO DO is clearly related to the third TO DO at this stage (“Reconnect to stakeholders”).

For most smart city and low energy district projects, the city administration is in a central position. Therefore leadership and political approval go hand in hand, and are crucial for a successful start and the realisation of the project. Besides, the buy-in of key stakeholders is needed: the proposed projects alter their living environments, and from a legal perspective, their approval could be even mandatory. What is more, stakeholders might have to bear a part of or the entire the financial burden. For all these reasons, stakeholders should be explicitly asked for approval, support and commitment, next to the city’s administration.

TO DO 9: PREPARE THE MONITORING PROCESS

by considering KPI’s for targets and co-benefits

Now the most viable project proposals have been selected, preparation of the monitoring process can start. Usually this happens at interdepartmental city level with the help of sectorial experts.

Monitoring is a necessary step for action plan and project management and permanent improvement. In the case of smart and sustainable cities and communities’ projects with a holistic approach, monitoring helps in achieving a consistent and systematic evaluation process:

- It clarifies programme objectives;

- It links activities and their resources to objectives;

- It translates objectives into performance indicators and sets values for targets;

- It routinely collects data on these indicators;

- It compares actual results with targets;

- It reports progress to managers, authorities and citizen;

- It alerts them to problems.

Translating objectives into performance requires an appropriate set of indicators, known as KPIs. These KPIs are characteristic indexes to be measured. They can vary enormously: from number of people using public transportation, temperature in buildings, number of public consultations, number of green areas and total surface, number of KWh produced by renewables, annual weight of residual waste per inhabitant, share of the population with internet access, annual GHG emission, number of e-vehicles in self-service, to air quality, noise levels, etc… KPIs can be either quantitative or qualitative.

At this stage, KPIs are considered which reflect progress, not only on the targets as defined early during the PLAN stage, but also capture co-benefits other than reduced fossil fuel consumption or less GHG emission: additional benefits, not only for citizens and other stakeholders (e.g. improved public spaces, less energy poverty, less air pollution), but also for the city administration itself (e.g. lower operational expenditures, smoother inter-departmental collaboration).

That the gathering of data for monitoring of smart city and low energy district projects, can easily lead to issues in the field of data privacy, was confirmed in interviews conducted for this guide. Smart city and low energy district projects often focus on data as a way to track activities, measure consumption, learn about usage patterns, and optimize solutions, but maintaining the trust of public and private entities with regards to privacy is of paramount importance in order to further these concepts. The project should be transparent about its data collection and use policy. One key player recommends that every dataset includes privacy considerations in its design and implementation. Privacy needn't dominate the discussion or lead the conversation astray, but it should be treated with the respect and importance that it deserves. Another key player stresses that open data should always be aggregated data and under no condition contain private information.

A standardized approach to data privacy could help resolve some of the apprehension and resistance to sharing information, but this "would need to be quite complex, since privacy within a dataset can be compromised by comparing data from other datasets", according to an interviewed key player. Other possibilities are application of technical measures as encrypting and improved security of for instance smart meters. During hackatons security of planned or deployed technology can be tested, and subsequently improved.

EXAMPLE: SMART PLATFORM FOR MONITORING

SmartKalea is an innovative initiative of Fomento San Sebastián that establishes a public-private collaboration model that integrates all agents that co-exist in a city environment from a Smart perspective: citizenship, businesses, technological local companies and Municipal Departments, lead by Fomento San Sebastián. It consists of a pilot project based on Smart implementations to test and validate a comprehensive model, for its expansion to other geographical areas and turn Donostia in a Smart City reference.

More specifically, SmartKalea promotes environmental sustainability, energy efficiency, citizen participation and transparency using state-of- the-art technology from local technological partners, integrating data into the project's smart platform for monitoring and obtaining indicators that promote the improvement of the management of the city. The SmartKalea project was launched in 2014 in Mayor Street, an iconic street of the Old Town of San Sebastian. The good results of this first pilot have allowed the continuation of implementations and the replication it in other areas of the city. In 2016 the project was expanded to the whole of the Old Town and was replicated in the Altza neighbourhood. Funding from the Regional Government (Diputación Foral Guipúzcoa) was received for the replication in the Altza neighbourhood. SmartKalea will continue implementing smart solutions in different streets and neighbour of the city such as Sancho El Sabio in the Amara neighbourhood (Fomento San Sebastian, 2019).

EXAMPLE: TRANSPARENCY OF OPEN-SOURCE DATA

Boulder, Colorado's IT department conducted a thorough "review of data schema and record refresh plans before publishing their open data website. This included developing licensing terms including terms of use, attribution and a disclaimer" (Bent et al., 2017). The city is a founding member of OpenColorado,, a collaborative project with other local governments sharing transparency strategies and providing open-source data and public information (OpenColorado, 2017; Bent et al., 2017).

EXAMPLE-GLASGOW

Scotland's Open Glasgow programme, embedded a "new culture of 'Open by Default' within Glasgow" where the City Data Hub addresses "concerns about privacy and data quality and maintenance … by providing a configurable workflow that includes validation checks, and automated publication from business systems” (FCG, 2017). "'Improved transparency, communication and collaboration by opening up data are significant factors in the smart city journey; one that Glasgow has undertaken and one that cities around the globe are pursuing' Pippa Gardner, Programme Manager, OPEN Glasgow" (FCG, 2015).

WHY?

Access to data is one of the core principles of many smart city projects. Interviews with key players confirmed that collecting and processing data, promoting collaboration, and providing access to that data, while maintaining privacy, have become a common issue in smart city and low energy district projects

Some projects have found that not only are regulations concerning "data usage, protection, gathering and re-use of public sector information" inadequate, but existing regulations suffer from issues of noncompliance (Interviewee #1, 2017; Interviewee #2, 2017; Stacey et al., 2016a). Main concerns regarding data privacy shared by the interviewees are as follows:

"Maintaining privacy of data while promoting interoperability is an issue" as are: "Property rights and privacy regarding prototypes" "Protecting the data itself" and "Gathering enough information, while remaining with the law regarding the profiling of people – which is forbidden by law".

"…every new dataset needs to consider privacy…never-ending but not enormous. It needs to be discussed and resolved with every dataset." "Privacy shouldn't be a showstopper…but it shouldn't dominate the discussion. It can lead the conversation astray" "Give the issue of privacy its proper place…not ignored but a showstopper…don't let the concern get out of hand and hinder progress on the issue".

"…the ones who are really concerned about privacy – including the project promoters and managers…so some of these are internal obstacles that are welcome in a way – you want to put out a good product that doesn't compromise security/privacy".

"Need to maintain trust…accept the concerns of the public/private…Worry about losing the trust of the public".

"Standardisation of approaches to privacy within datasets could resolve some of the resistance or conflict" "…but this would need to be quite complex, since privacy within a dataset can be compromised by comparing data from other datasets".

"on one hand, you want to collect a lot of information to make a smart city...on the other hand you don't want to infringe on people's private information".

TO DO 10: PREPARE IMPLEMENTATION

through own fi nance and funding, contracting public procurement and PPPs

The last TO DO for this stage is to start preparing contracts, public procurement, and public-private partnerships. Cities often have in place existing practices for procurement (the public purchase of work, goods or services from companies), but these are often incompatible with innovative solutions. They are based on an existing model of provision, and therefore support the business-as- usual situations better.

One approach to promote innovative solutions is to tender calls for solutions instead of specific products or services – in this manner the solution provider is allowed a wide range of options to meet the guidelines of the tender, and may develop new solutions outside the expectations of the tender (Stacey, 2016). Another approach is to include criteria for sustainability as energy efficiency, re-use and clean energy production in public procurement.

EXAMPLE: FROM PROCURING GOODS AND SERVICES TO PROCURING SOLUTIONS

"A move from procuring goods and services to procuring solutions to a challenge. This is one new tender model that seeks to form a relationship and increase collaboration between the customer and suppliers and between suppliers. Using the responses to tenders to refine and add value to the proposed solutions from the private sector is an iterative process that builds capacity in both the customer and the market. It also uses the city as a testbed and demonstrator for new processes and technologies allowing and encouraging further replication and shared learnings across the public sector" (Stacey et al., 2016a).

EXAMPLE: FAST-TRACKING HIGHLY STRATEGIC SUSTAINABILITY INITIATIVES

"[Washington] DC’s complicated procurement process can take six to nine months. When funds must be spent within 12 months, sometimes there is not enough time to complete the actual work. Recognizing the delays in contract procurement, the District Department of the Environment created a Green Building Fund Grant Programme for highly innovative projects. The grant allows the city to move more quickly than the traditional procurement process and fast-track highly strategic sustainability initiatives. The grant is currently funding projects to perform quality control for its energy benchmarking programme, create a “smart buildings plan” for the city, drive innovation in the green appraisals market, green real estate listings for residential properties, and develop the DC Smarter Business Challenge – a green business competition platform" (Bent et al., 2017).

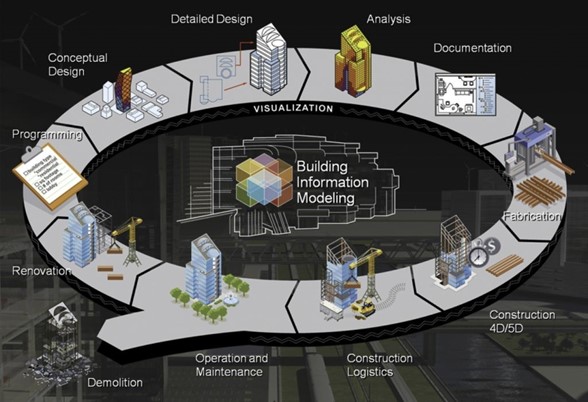

EXAMPLE: BUILDING INFORMATION MODELLING BIM AS REQUIREMENT IN PROCUREMENT

The European Public Procurement Directive 2014/24/UE, Art. 22 states: “For public tenders and designing bids the member states may ask the use of specific electronic instruments like electronic simulation instruments for the constructions information or similar instruments” (EC, 2014c).

To quote an example, recently the Italian Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport worked on a draft decree governing the obligation to use Building Information Modelling (BIM) in the design of public works. The new Code of Conduct for public procurement introduced mandatory specific design methods and electronic tools, such as modelling for building and infrastructure, as required by European legislation. This obligation is aimed at rationalizing design activities and related verifications, by improving and streamlining processes that influence contracting. According to the text, the obligation will gradually enter into force: from 1 January 2019 for complex works relating to works of an amount equal to or greater than 100 million euro, on 1 January 2025 for all new works. Electronic modelling - the Ministry explained - is a paradigm shift in the construction sector that will allow rationalization of investment spending, internationalization of professionals and businesses, and will help to make the sector more efficient and transparent. The process, known and already applied as BIM, is a model for optimizing, through its integration with specific electronic methods and instruments, the design, construction and construction of buildings in the infrastructure sectors. Through it all relevant building data that is present at each stage of the process must be available in open and non-proprietary digital formats.

BIM becomes a powerful instrument to increase communication, certainty and transparent information-sharing. It helps to reduce risk, increase productivity and see how the project is evolving and being built. When collaboration is needed between multiple contractors, design teams and owners, BIM is a means to coordinate them and track the project reducing of 50% the project risk management.

There are many variations of procurement methods that depend on the client, their scale, sector, stage of maturity and attitude to risk. Using BIM there is an opportunity to improve information management assistance in public procurement processes, BIM can be used in collaboration at all design, construction and operation phases. This assistance can begin with the creation of a shared data environment, so that model-based sharing of information could be included in the collaborative BIM procurement process (Bolpagni, 2013). \

(2016)

EXAMPLE: PUBLIC SECTOR COMPARATOR

In Public Administration, the Public Sector Comparator (PSC) is a tool used by public administration in determining the proper service provider for a public sector project. It consists of an estimate of the cost that the government would pay were it to deliver a service by itself. The World Bank has its own definition, wherein a PSC "is used by a government to make decisions by testing whether a private investment proposal offers value for money in comparison with the most efficient form of public procurement." Generally, the PSC allows governments to figure out if a public–private partnership or other arrangement would be more cost effective.The PSC is most commonly used in UK. The city of Genova has recently obtained an ELENA project using PSC.

WHY?

WHY? Public procurement processes are seen by many projects as being a cumbersome and complex procedure that involves too many stakeholders and intimidates project developers (CITYnvest, 2017; Rivada et al., 2016).

Existing procurement models discourage innovation in both products and services by having a rigid model of providing for the specifications required (Stacey, 2016). Municipalities have little experience with alternative approaches, such as Public Procurement of Innovation Solutions (PPI) and Pre-Commercial Procurement (PCP), and therefore are unaware of the potential benefits (Rivada et al., 2016). "Public bid procedures can be very time consuming" (Interviewee #1, 2017). Regarding procurement – there is not really a specific actor tied to the obstacles, but more a problem of untangling the complexity (it's too difficult) (Interviewee #2, 2017).