TO DO 1: COMPOSE A SKILLED LOCAL TEAM

with representatives of the city administration and stakeholders with roles and responsibilities

The execution of the action plan or project might require different competences and capacities than its preparation. Therefore, for the second time a skilled local team must be composed. This team should have representatives of the city administration and key stakeholders on board, with roles and responsibilities in the assigned action plan and/or project are agreed upon and clearly described. It can be the same team as the team that worked on the preparation of the plan, but not necessarily so as other competences and skills, or other roles and mandates, might be needed for implementation of the plan. The responsibilities and mandates of the team members must be clearly related to the structures (organograms) of their respective organisations. Staff competency and capacity are crucial for successful implementation of action plans or projects. Therefore, the chosen team must not only have the technical and organisational competences and skills to realise the plan, but this must also be in sufficient quantities. While in theory, smart city and low energy district projects should be rearranging the city workload and not adding to it, this may not be easily visible in the first stages of project implementation. The best advice for this challenge is to prepare accordingly. This includes checking to make sure that commitments from internal and external partners have a solid basis and that there is enough talented, and flexible, staff to accommodate project needs. Once the commitments are checked and the available staff is compared with the necessary staff, in both quantity and competency, the budget may need to be revised in order to accommodate additional training or hiring of staff. Especially technical or interdisciplinary competences in the city administration might fall short of what is needed (see for example OECD, 2016). Easy options for (post-graduate) training might be the establishment of curricula or academies with local research institutes such as universities or RTO’s. Lastly, the exchange of personnel in collaboration with (local) businesses, and traineeships and internships might be helpful to raise the technical competences of the staff.

MIGUEL GARCIA-FUENTES, RESPONSIBLE OF ENERGY, STRATEGY AND BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT CARTIF

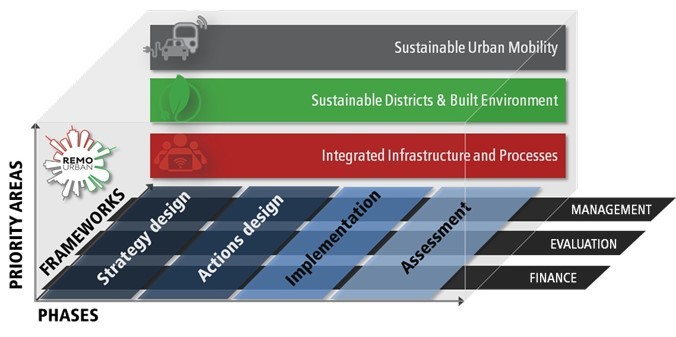

The Urban Regeneration Model from REMOURBAN supposes a step beyond current practices in the field of addressing cities’ sustainability and smart transformation. It integrates mechanisms to empower the stakeholders that belong to this process at the different stages, while provides mechanisms to define, implement and evaluate integrated strategies for these ecosystems.

The Urban Regeneration Model from REMOURBAN supposes a step beyond current practices in the field of addressing cities’ sustainability and smart transformation. It integrates mechanisms to empower the stakeholders that belong to this process at the different stages, while provides mechanisms to define, implement and evaluate integrated strategies for these ecosystems.

EXAMPLE: DIFFERENT ROLES AND ACTORS PER STAGE FROM PLANNING TO IMPLEMENTATION

The Urban Regeneration Model (URM) developed within SCC-01 REMOURBAN project, provides solutions in both technical and non-technical fields addressing the long-term goals, the main Smart City enablers within urban transformation processes and innovations in the priority areas of energy, mobility and ICTs. Its main objective is to accelerate the transformation of European cities into smarter places of advanced social progress and environmental regeneration, as well as places of attraction and engines of economic growth. The URM defines a procedure composed of several phases and decision-making processes which define the city’s objectives and translates them into a set of strategies for a sustainable and smartness-oriented regeneration of the city. By providing better tools and mechanisms, URM improves communications among stakeholders and contributes to better decisions.

Especially interesting is how, during the implementation stage, the combination of the overall Integrated Urban Plan, a preferred urban development scenario, and a proposed Action Plan are translated into an Implementation Plan. A profound diagnosis of the current situation in the area where the intervention is planned and an establishment of the baseline information, next to a detailed design for the area of the planned interventions, are key elements in this. In all stages, the URM methodology pays special attention to management, assessment and evaluation of impact, and financing of urban transformations. Per stage, different roles and actors are driving the results. Regarding management, during the action design phase, co-ordination committees, knowledge institutes and transformative alliances steer the process of action design. During the implementation stage the commitment of major political groups, different stakeholders and the general public is critical. A design team of engineers and architects plans the interventions and implementation of projects, while a contractor is responsible for site management. Local governments check whether the proposed interventions fit their long-term goals, while financial institutions will appoint a certifier to ensure the planned performance of the project. The five REMOURBAN cities (Valladolid, Nottingham, Tepebasi/Eskisehir, Seraing and Miskolc) have been working towards designing and implement different stages of this model, benefiting from it and leading to deliver Integrated Urban Plans and Action Plans for their cities (REMOURBAN, 2018).

EXAMPLE: EDUCATION OF MUNICIPAL STAFF IN ENERGY TRANSITION

"Municipality staff including planners, district level regeneration management and economic development teams have often yet to have the training in how to successfully bring about a transition to low energy for an urban area. The collaboration of industry and academic bodies to catalyse the learning processes within local authorities has produced effective dissemination of new ideas across fast paced areas of change such as healthcare and low energy should be no different" (Rivada et al., 2016).

WHY?

For a well-equipped team, existing staff should possess sufficient technical and organisational competency, as well as have sufficient staff resources at its disposal, in both time and numbers.

Staff competency and capacity are tricky issues to deal with at the level of project implementation. The lack of capacity in either subcategory is difficult to remedy in the time span of project implementation. Public hiring practices may suffer from the same complexity or convoluted process as other administrative issues, resulting in a possible delay in project implementation if requirements are not caught early enough and remedied quickly.

TO DO 2: ALLOCATION OF RESOURCES

to the team(s), such as budget, capacity etc.

The next TO DO is that of resources, such as budget, capacity, workplace, etc., must be allocated to the team(s). There can be more teams working in parallel on different parts of the action plans and/or projects at the same time. These resources can be made available by the city administration, but also by stakeholders, investors and other financial parties, or regional and national government. The budget will most probably include expenses for acquiring specific technologies or for contracting construction or refurbishment works. PPPs can make specific arrangements among their partners. A part of the resources might be covered by subsidies, research funding or pre-commercial procurement. Further, by relating the action plan or project to smart specialisation strategies, it might receive regional economic incentives. Many smart city and low energy district plans combine different forms of finance and funding to develop a solid business case.

EXAMPLE: RESERVE HOURS FOR STAFF BEING PART OF THE IMPLEMENTATION TO FOSTER PARTNERSHIP AND LEARNING

SCC-01 project Smarter Together proved that partnership between governments, citizens and businesses liberates huge potentials that are not possible in a conflict-oriented societal context. Partnership provides also the environment for learning and organisational development and motivates actors to make their contributions. It also strengthens the credibility of governance and politics that is so crucial for getting the citizens/inhabitants on board and creates positive social dynamics. Process- oriented learning on the spot is much more efficient than imposing top-down solutions in an environment with possibly mistrust. It is also much more motivating. This is a major change in the communication culture amongst actors and the perception of the “other”. Smarter Together demonstrated that small steps rather than big unrealistic claims provide the actors the trust-worthy environment of learning without being criticised. Through the process, all actors learn and increase trust in the other. This fosters positive social dynamics. All project activities are a playground for integrative communication as well as for the development of a positive organisational culture. Communication, awarding and motivation target the human dimension of development.

Smarter Together Vienna determined from the start a sufficient amount of person months in the project management plan in order to enable staff to be included in the implementation process rather than only in the implementation of minimal tasks. Project partners have on one hand clear targets. On the other hand, the project environment provides the framework for creativity that is awarded through communication (for instance project website and newsletter). The involvement in the project of staff from different departments stimulates interdepartmental cooperation beyond the usual competence-oriented cooperation. At the same time, international cooperation provides a wider visibility and importance to local action that is motivating locally.

EXAMPLE: APPROVAL OF PROJECT PLAN BY THE CITY COUNCIL WITH THE BUDGET

When asked the question "If the project were to start now, knowing what you've learned so far, what would you have done differently?" one interviewee was very quick to reply: "Well I think I would have started with more staff. This sort of project should not be started with only one person. I also would have presented it to the city council with a budget. And of course, if you want a budget you also have to define goals. So, make it measurable from the beginning " (Interviewee #5, 2017).

WHY?

Staff capacity refers not only to the competencies of the staff but to the quantity of available resources, in both available working hours as well as number of competent people.

Many smart city and low energy district projects have found that a lack of available staff within city administration or relevant public institutions that have the experience, skills, or ability to deal with innovative initiatives and solutions is often a limiting factor (BEEM-UP, 2017; Rivada et al., 2016). Innovative or integrated projects in the field of smart cities and low energy districts may also be very time-consuming tasks, requiring the attention and commitment of dedicated staff (CITYnvest, 2017). Finally, implementation of smart city and low energy district plans might require additional finance, so costs of investments should be justified in the budget and not be underestimated.

TO DO 3: DRAFTING A DETAILED ACTION AND/OR PROJECT PLAN

by defining actions in dialogue with the stakeholders

Subsequently, a detailed action and/or project plan has to be drafted with the help of standard project management tools for the next TO DO. Standards project management tools provide a wealth of information on this.

WHY?

The detailed action and/or project plan explains comprehensively what has to be done in what way, within a specific timeframe. Besides, it clarifies the tasks and responsibilities during the implementation phase. Finally, it makes it possible to track the progress of the project with the help of monitoring.

TO DO 4: ORGANISATION OF THE KICK-OFF

of the action plans and/or projects

After this, a plenary meeting of the city administration with preferably all stakeholders must be organised, for an official kick-off or start of the action plan and/or project. This could also be in the form of public meetings or hearings, if possible on the site of the smart city or low energy district plan.

EXAMPLE: SIMMOBILE, A MOBILE URBAN LIVING LAB

Although technically not a traditional project kick-off meeting, the SIMmobile which the City of Vienna used in Smarter Together, proved to be highly successful in engaging citizens and other stakeholders in comparison to more traditional hearings. The SIMmobile was set for a period of 3-6 week in a row (2-3 days a week) on public places related to the project implementation. Numerous local institutions were also invited to use the ULL as a tool for self-promotion. Specific children focus was developed too. Surveys on variable levels were made. For instance, pupils of the school that had been up-scaled in the project were asked about their wishes with respect to the design and installations of the future building. Employees of the biggest industrial site (Siemens) were asked about their mobility ideas. In both cases, the results were transferred to decision makers, architects and the managements. As a result, inputs and ideas were taken into account and partly implemented. Special gamification tools were developed too (energy quiz) or workshops provided (by Science Pool). The SIMmobile provided an opportunity for communication with citizens that would have never been reached out in the closed set-up of its few branch offices in the city.

WHY?

This meeting has several purposes. It marks the official launch of the action plan and/or project.

Also, participants get a shared understanding of the project’s ambitions, in case they might not yet have been fully up-to-date on this, and the selected actions being used to achieve these ambitions. Participants can relate to the proposed actions to their own responsibilities and competences, to further prepare for their role in the action plan or project. A proper kick-off meeting can contribute much to team-building, especially when team members meet their fellow team members for the first time. From a communication viewpoint, it increases the external visibility of the action plan or project and enhances the smart or energy efficient city brand of the city and community.

TO DO 5: SET UP THE MONITORING PROCESS

by defi ning the baseline information, defi ne monitoring methods and protocols in detail, choose KPI’s

Successively, the earlier preparations of the monitoring process during the PLAN stage must be elaborated in more detail. A very important part of this TO DO is that a “snapshot” of the current situation should be taken, the so-called baseline, for comparison of KPIs during the CHECK stage (see also section 5.3). In addition, qualitative and quantitative KPIs, including financial and performance indicators, must be finally chosen after consideration at the PLAN stage. Advanced Horizon2020 SCC-01 projects advocate the inclusion of some KPIs and value capture techniques for process learning as well, as this appears to be less often highlighted, but a major positive outcome of SCC-01 projects (Evans, 2019). Once the KPIs are known, the methods and protocols for monitoring should be defined in detail. Data collection for the baseline can start after it is clear which methods and protocols should be used.

Key Performance Indicators

As explained earlier, KPIs are relevant indicators that have been selected for ensuring the agreement of stakeholders on targets, on evaluation and on monitoring. Indicators can be either quantitative or qualitative. The values of indicators must be assessed following standardised methods, as this facilitates comparisons between different action plans or projects. This feeds a benchmark of best practices, and helps in defining targets for action plans or projects about to start, based on validated success stories.

Several management systems and initiatives for a smart and sustainable development of cities and communities have been implemented in Europe and even worldwide, in particular the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy (CoM), the European energy award (eea) management system, EUROCITIES’ framework, Horizon2020 CITYkeys project, the Smart City Information System (SCIS), and Horizon2020 ESPRESSO project. These management systems, projects and initiatives have been engaged as active partners within the EIP-SCC and collaborated intensively in workshops and meetings to define basic sets of KPIs for smart, sustainable and energy efficient cities.

While there are many different types of European cities and communities in terms of size, domain of responsibilities, development, culture, historical context and local specificities, the overall picture is that specific sets of KPIs can be proposed and serve as a point of departure for all other city administrations, while being flexible enough for different situations and conditions. So far, four different purposes for KPI usage, each with a different scope, have been identified:

- Programme evaluation and management (more overall view)

- Project evaluation and management (rather sectorial approaches)

- Reporting and communication (internal and external, including to citizens)

- Benchmarking related issues (feeding a benchmark of best practices and success stories)

For each of these purposes, five main categories of KPIs have been defined, common to all programmes, projects and action plans. These main categories can be subdivided as follows:

Category 1 – PEOPLE: health, safety, access to services, education, social cohesion, mobility, noise and silver economy;

Category 2 – PLANET: energy, climate resilience, water, waste, pollution and ecosystem;

Category 3 – PROSPERITY: employment, equity, green economy, economic performance, innovation, attractiveness and competitiveness;

Category 4 – GOVERNANCE: organisation, community involvement, training, procurement, multi-level governance, development and spatial planning;

Category 5 – REPLICATION/SCALING-UP: scalability, replicability, local co-operation and cross-cities/communities co-operation.

It is advocated to take these KPI (sub)sets as a point of departure when the monitoring process is actually set up in the DO stage, and KPIs have to be chosen.

EXAMPLE: EUROPE-WIDE KPIS FOR SMART CITIES

The CITYkeys Framework is a means for strengthening European smart cities strategic planning processes, monitoring their progress and collecting the cities’ experience. Within the framework, CITYkeys developed two sets of indicators, the first level of indicators is about the cities and the second level is about projects (Huovila et al., 2017). The CITYkeys Performance Measurement Framework supports the following activities among others:

- Monitoring of the progress in urban development and ongoing projects;

- Evaluation of projects after completion;

- Measuring changes in the city after implementation of the smart city project;

- Comparing the existing situation (baseline) with the expected impact;

- Stimulating cross-departmental collaboration;

- Comparison of projects with each other while tracking one’s own projects’ performance;

Tracking the progress on overall policy goals of a city and provide a benchmark for comparing cities with each other.

WHY?

The importance of comparable KPIs for monitoring and benchmarking is commonly acknowledged, and several models and sets of KPIs have been developed and are in use today.

However, the larger part refers to measuring the outcomes of actions as part of an evaluation afterwards or for making comparisons, without using these KPIs to actively follow and steer progress during implementation. Only a limited number of approaches and initiatives cover the entire sequence of stages in setting targets and following progress, in helping to develop a consensus-based strategy, in managing its integrated plans, in improving collective awareness and in contributing to new organisational and governance models that are results-oriented.

An overview of these few integrated, cross-domain management systems:

- The European Energy Award quality management system has been developed by cities for cities. It has been implemented for more than 25 years, in approximately 1500 cities and communities so far;

- The Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, with close to 8000 cities and communities committed in Europe, and 6000+ SEAPs (SEAPs) and SECAPs (SECAPs) already developed, thanks to a strong political commitment;

- More recently, ISO has developed a sustainable communities management system – ISO 37101 - with the same concept as other ISO management systems (e.g. ISO 9001, 14001, 50001). These ISO standards and eea model are fully consistent, and can be implemented simultaneously; more importantly even, eea can play a major role in preparing the scene by fostering a culture of holistic, integrated management, such as for ISO 50001 or ISO 37101 implementation.

These models of management systems are also very useful for raising awareness among all stakeholders and for knowledge transfer, thus providing all interested parties with an improved level of knowledge and appreciation of what smart sustainable urban development entails. This is essential for achieving consensus with regards to vision, strategies and objectives.

Main initiatives advocating implementation using KPIs for tracking and steering, but also for strengthening mutual collaboration, are the following:

- Citykeys H2020 project;

- SCIS;

- ESPRESSO H2020 project:

- The European Energy Award and its set of KPIs;

- The Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy initiative with SEAP and SECAP targets;

- Standardisation with, among others:

- ISO 3712x series of indicators, for smartness, for sustainability, for resilience.

- ITU U4SSC model, in as tool for UN Sustainable Development Goal 11 (smart cities and communities)

- For the development of sustainable communities. These are also available in some countries in contextually adapted versions

- BREEAM Communities: Criteria and methods for selecting and deciding upon criteria

TO DO 6: START ORGANISING ACCESS TO AND SHARING OF RELEVANT DATA AND PROJECT INFORMATION

through an urban platform

The next TO DO is that the team must start with organising access to, and sharing of, relevant data and project information through an urban platform. Data availability, modes for sharing, and interoperability can be difficult issues to solve during the implementation of smart city and low energy district plans.

There are several ways municipalities can work to improve data availability and interoperability, and enable the sharing of data to facilitate innovation. The development of a standardised protocol for data interoperability between localities could solve many of the issues of different cities and organisations adopting different protocols (Stacey et al., 2016a). The statistical office of the country could be tasked with providing access to the data, maintaining its quality, structure, and interoperability (Di Nucci, et al., 2010). Municipalities often lack the staff or technical capacity to create and maintain open data services in house (Rivada et al., 2016), but the scale of these needs would be lessened with a standardised approach involving built-in interoperability.

Other solutions entail development and application of standards, and development of shared urban platforms. For instance, the FIWARE open source initiative defines a universal set of standards for context data management, which facilitate the development of Smart Solutions for different domains, such as Smart Cities, Smart Industry and Smart Energy (FIWARE, 2019). FIWARE standards are applied in several SCC-01 projects (see section 4.4).

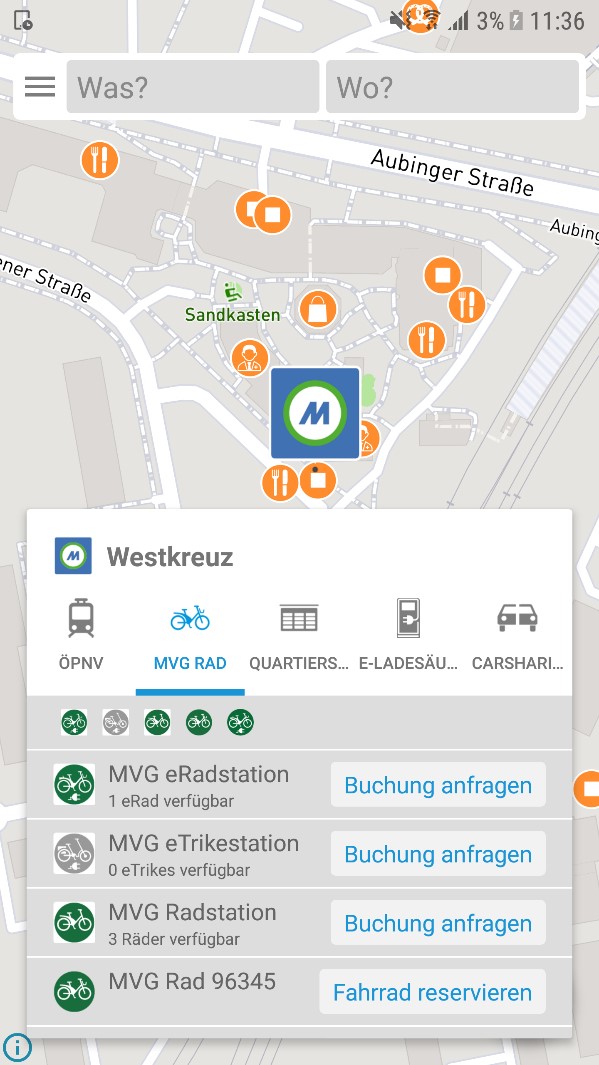

EXAMPLE: MUNICH SMART CITY APP

The Munich SmartCity app is an example of how to make an existing offer smarter – within the Smarter Together project the Munich app became the Munich SmartCity app in January 2018 by adding additional smart services as well as a more user-friendly design.

The new smart app services are worth a closer look: When a user opens the app, the home screen displays information about their current location and smart services offered there. Mobility service is one of the central functions of the app: In the interactive city map they can find public transport, cycle hire, car sharing services, and pedestrian paths. Another central function is the integration of digital municipal services (eGovernment services). Apart from the new services, the app provides users with tips on top sightseeing spots, events and the cinema program.

Additionally, the Munich SmartCity App is the central access point for services and smart data from all the innovations developed within the Smarter Together project that are of interest for Munich citizens – for example the measurement data concerning air quality or parking information measured by sensors that are fixed at the smart lampposts installed in the project area.

EXAMPLE: IN-HOUSE KNOWLEDGE OF TECHNOLOGY AND PROCUREMENT TO PREVENT VENDOR LOCK-I

"Bristol is alert to this issue. 'We are not going to rely on a vendor to sort this out for us,' says [Paul Wilson, managing director of Bristol Is Open, the smart city unit for Bristol, England]. "If you outsource to a consultant, you can end up with lock-in. The local authority has been astute enough to hire people with quite sophisticated technology and procurement backgrounds to say: we are the city and we are the platform. We know our strategy and we will go to vendors to fulfil aspects of our strategy." (Pringle, 2016b).

EXAMPLE: ELECTRIC MOBILITY MANAGEMENT PLATFORM FOR E-TAXIS

In Florence the transport sector has the largest impact on GHG emissions, with 34.5% of total CO2 emitted. The city, congested as it is by commuter and tourist flows, needed a substantial, integrated action to achieve the significant reduction in the environmental impact of its mobility targeted for 2030 in its Smart City Plan. In recent years, policies consisted of both the technological modernization of the circulating fleet and the promotion of low-impact mobility and public transport. As part of that, e-mobility has been promoted for 20 years now, since the first charging pole in Italy was installed in Florence: starting from the public tramlines, the municipal fleet, the e-sharing service, the public recharging network and several incentives such as free parking for e-cars. Supporting measures, such as a Smart and Resilient Grid and a Smart City Control Room, have been deployed in parallel to enable this transition of urban mobility. As a part of public transport, the taxi fleet presents particular needs in terms of autonomy and charging periods while it is a powerful dissemination channel for e-mobility to city users. In the REPLICATE SCC-01 lighthouse project, the switch to electric vehicles of the public taxi service has been propelled, not only to increase its sustainability but also to promote the electric mobility to city users.

In the partnership, the city administration regulates the public service, defined the sites of the Enel Fast Recharge Plus, and created exclusive areas for new e-taxis recharging. E-distribuzione has selected the technology and is responsible for its management during the SCC-01 project, while Mathema has developed an app for taxi drivers. With the app, taxi drivers can choose the superfast charging pole, choose the plug and book, and it will be blocked and reserved for the taxi driver who booked. The municipality published a dedicated tender exclusively for e-taxi service (70 new licenses dedicated to e-vehicles) with a 25% discount and provided agreements with vehicles producers for special purchasing conditions. In parallel, e-distribuzione installed six new Enel Fast Recharge Plus 1G (EFRP) charging stations, for exclusive use of taxi in public areas identified together with the Municipality and with the taxi drivers’ association. The stations have been installed at crucial transport network nodes, for example near the main station, the airport and the main access points to the city. The EFRP charging stations are fully integrated in the low voltage distribution network in a “smart way”, ensuring the security and the stability of electric system, with the possibility to modulate the current of each charging, thanks to the remote control by the Electric Mobility Management (EMM) Platform. Through the EMM Platform, all charging stations are managed in an interoperable way, non-discriminatory access and multi-vendor approach, thanks to the smart meter technology, thus assuring benefits to the end-user guaranteed by free market competition. The full integration of the electric vehicle supply equipment in the low voltage distribution network and the management based on the EMM Platform provide the possibility to manage in a better way energy flows avoiding networks overloads on one hand and, and enabling new customer experiences based on innovative services and solutions in other hand, such as:

- the possibility to identify the closest fast charging point and reserve it through mobile phone (Mathema’s app available for taxi drivers);

- monitoring and controlling of charging process;

- load modulation;

- payment of charging directly in the bill, according to the tariff profiles signed with the drivers’ own retailer.

This will foster the development of electric mobility without compromising the safety of systems and the quality of supplying for other customers.

EXAMPLE: SMART DATA PLATFORM AND DATA GATEKEEPER CONCEPT

To save energy, reduce CO2 emissions and facilitate a cleaner, cleverer flow of traffic and many other challenges, for a smart city the use of digital technologies is indispensable: for up-to-date information, communication, data exchange, planning, analysis and connectivity. The City of Munich, in the context of the Smarter Together project, has built a “Smart Data Platform” to collect and handle all generated smart city data accordingly.

The “Smart Data Platform” offers several interfaces to enter the data from different use case scenarios of the project Smarter Together (e.g. energy, sensors and mobility stations). Data formats and protocols are all based on open standards. The platform allows analysing the available data and provides the results into an analysis dashboard. Selected results are accessible for a broader public via the Munich SmartCity app. Depending on the use case, the platform’s analysis engine can combine several data sources and merge the information to show dependencies and patterns between the different sources of information.

The City of Munich, a trusted authority for the administration of data, has committed itself to involving all relevant stakeholders and defining suitable conventions and rules in the context of possible fiduciary and business models relating to the use and provisioning of data. This information and these transparency rules were described and discussed in a “Data Gatekeeper” concept (which can be made available for cities interested in developing smart city data concepts). This paper contains extensive recommendations, “golden rules” and guidelines on trustworthy dealings with data in the context of smart cities. Aspects of importance to all urban stakeholders – from a discussion of relevant paragraphs of the new European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to specific recommendations for technical implementation of rules in the context of data platforms – are sketched in the document.

Finally, a “Transparency Dashboard” was designed to describe all sensors, data analysis mechanisms, and data handling aspects of the project in a most transparent way. The Transparency Dashboard is a Web-side, where Citizens and other interested people get a good project-related overview about which data is generated, how it is transferred and for which purposes it is analysed within the Smarter Together project (Transparency Dashboard, 2019).

WHY?

The limited interoperability of different data streams, platforms, and protocols, is a hindrance to fulfilling the full potential of many smart city projects, and, to a lesser extent of low energy district projects

Maintaining data access, availability, and interoperability while working with different vendors has also emerged as a looming issue. "Optimisation of ICT and integrated infrastructure will not be achieved if data is not shared and there is not commonality in platforms and protocols" (Stacey et al., 2016a).

Access to data is one of the core principles of many smart city projects. Collecting and processing data, promoting interoperability, and providing access to that data, while maintaining privacy, has become a common issue in smart city projects (Interviewee #1, 2017; Interviewee #3, 2017). One of the major concerns with urban information systems is the lack of consistently updated real-time spatial and temporal information required to maintain the utility of the decision-support system (Stacey et al., 2016b).

Furthermore, several projects noted problems with maintaining data availability and interoperability with private contractors – they fear being locked in to a proprietary platform or protocol provided by the outside vendor (Veronelli, 2016; Rivada et al., 2016). "In Spain, only some parameters to be measured and controlled are defined by regulations, but in general, there is a lack of normalisation for ICT systems in residential buildings. This fact is a source of difficulties for the Buildsmart project, which includes several numbers of different solutions, and the lack of standardisation makes the integration process more difficult. A special effort had to be made in order to ensure the correct integration of all solutions and the adequate performance of the building as a whole" (Mörn et al., 2016).

TO DO 7: EXECUTION OF THE PROJECT(S)

and management of progress

Finally, the last TO DO at this stage, is execution of the action plan or project, and management of the progress. From interviews it can be concluded that quite often smart city and low energy district projects have to make significant amendments and adjustments along the way, due to reasons varying from underperforming solutions to changed priorities of stakeholders that play a key role in implementation.

Often-mentioned is the fact that the implementation of the action plan or project can be hindered by several challenges related to regulations and legislative frameworks. The main issues are regulations that conflict with the project goals and lock-in, subsidies, and regulations that favour specific technologies (including competing solutions) or business-as-usual. Another issue is the complexity and possible conflict of regulations at different governmental and regulatory levels (e.g. local, regional, state, country, EU), for instance European rules on competition (Vandevyvere, 2018).

City managers need to direct the city policies and regulations to incorporate a more flexible approach - one that is more welcoming to innovation. This can start with allowing pilots and public procurement processes to permit temporary exceptions to regulations, to allow time for innovative, experimental, or disruptive approaches to test the market and see if there is a public demand for their services. By allowing these innovative approaches to test the field within a living lab, the city is able to set the ground rules for the demonstration site, as well as the parameters required for future expansion or approval of the project approach. Other solutions are to scan the regulatory and legislative framework during the planning and preparation to prevent an impact on the plan. Finally, a smart city plan or project should be encouraged to make proposals for adjustment of the regulatory framework, if needed.

EXAMPLE: AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES ONLY ALLOWED AS EXPERIMENT

"So there is an experimental clause, but we would like it to be more considered, so that we can do autonomous driving and things like that" (Interviewee #5, 2017).

EXAMPLE: ADJUST SOLUTION TO FIT IN REGULATORY AND LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK

"Regarding the specific intervention in FASA districts in Valladolid, the proposal has taken into account this obstacle. For this reason, the FASA photovoltaic facade will be connected to an isolated network off-line to avoid paying the toll circuit. The electricity generated by the facade will heat the hot water of the “tower building” through electrical resistance attached to the water tank"(Rivada et al., 2016).

WHY?

In some smart city and low energy district projects, existing regulations may create an impediment to the introduction of innovative, novel, or simply different technologies.

An example of this is with historic preservation rules and regulations that may impact the implementation (or cost-effectiveness of implementation) of energy technologies (e.g. rules requiring clay tile roof tiles where solar PV is not allowed, or exterior brick facades to remain and external insulation is not allowed). In some cases it is even unclear whether innovative approaches conform to the existing regulations, which may have been written in a different technological era (R2CITIES, 2017). A well-known issue in Spain is the Royal Decree 900/2015 on self-consumption of electricity (Ministry of Energy of Spain, 2015), requiring special fees for PV-generated electricity, and thereby discouraging investment in PV installations (R2CITIES, 2017; Rivada et al., 2016). Another issue is the refusal to allow "green" materials into the building code, so compliance with the law entails following the existing business-as-usual approach (Stacey et al., 2016a).

Rules and regulations may be introduced (or already exist) which provide a preference or commitment to specific technologies or approaches. An example of this was a project in Denmark where the implementation of district heating was impeded by a regulated commitment (lock-in) to purchase a certain quantity of gas supply: "…natural gas companies were given the exclusive right to supply certain heating areas in order to ensure that they could finance the development of a national pipeline system around 30 years ago"(Di Nucci et al., 2010).

The existing morphology of an area, including its associated infrastructures, may create an advantage for the business-as-usual scenario. It can be difficult for a new or innovative approach to compete when the infrastructure for a specific approach is already in place. This is visible with, for example, existing electricity infrastructure vs. district heating, or private vehicle on public roadways vs. expanding public transit.

One interviewee mentioned that national legislation and other legal frameworks do often not allow enough space for experimentation, for example in e-mobility projects. As a result, public administration, who are bound to legislation, cannot be as innovative as they want.